|

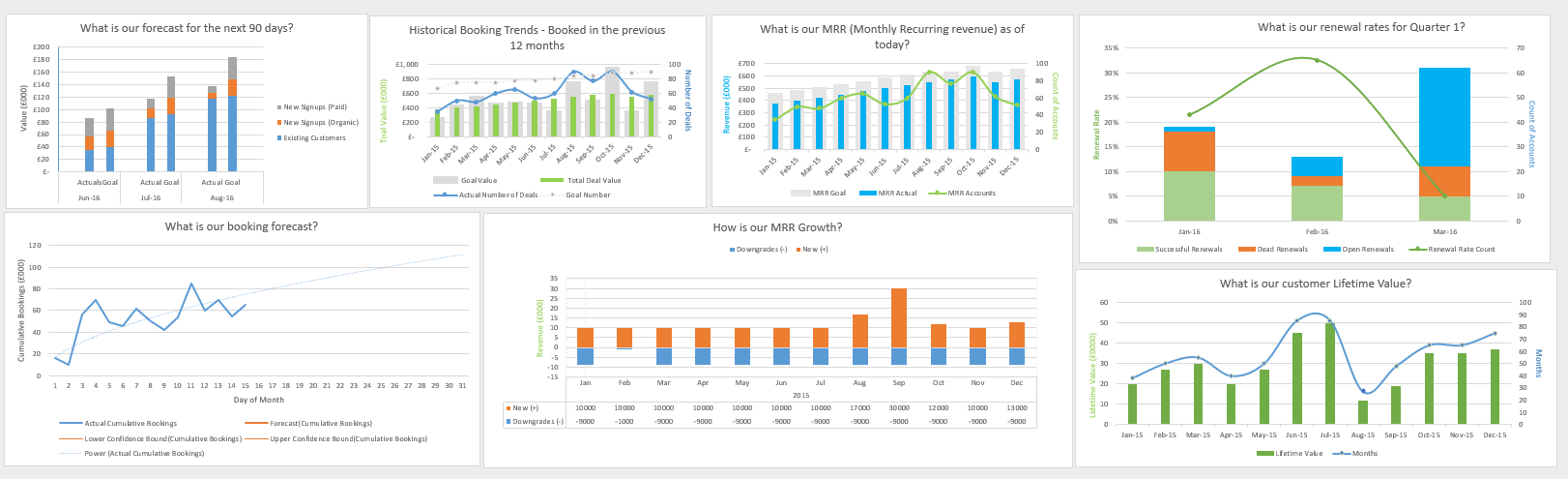

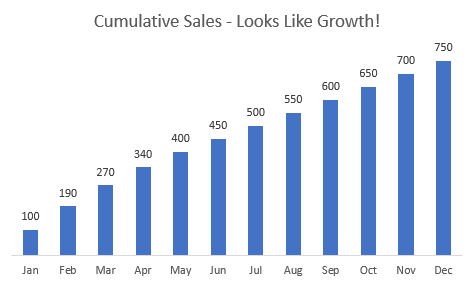

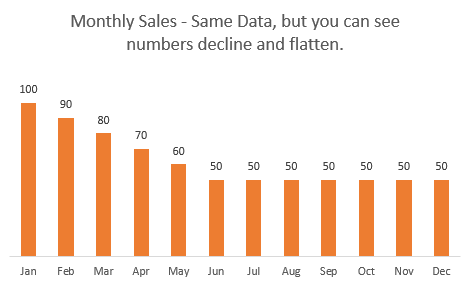

We’ve met more than 150 startups in Yangon and Mandalay and we continue to meet more every week as we seek the most promising early-stage companies in Myanmar. Over the course of these meetings, we’ve seen and heard some excellent pitches as well as some more confusing ones. We’ve noticed on a few occasions some confusion over certain terms when it comes to startup company metrics. Therefore, we thought it would be useful to clear up some terminology on business and finance metrics for startups. This isn’t a list of the only metrics you should be measuring. It is a list of things we know people get wrong sometimes. It’s also a list of the metrics that we like to see at first glance. These metrics tell us about the company and market potential and provide enough information to get us interested to learn more (assuming the numbers are good!). If anything remains unclear after reading, or prompts a question, contact us at [email protected]. Revenue or Bookings? Revenue is recognised once a service or product has been provided. Bookings is the value of the contract between the company and the customer. Let’s say you subscribe to receive a monthly milkshake for $5/month, you sign a twelve-month subscription for $60. The $60 represents the bookings for the milkshake seller. The milkshake sellers will then recognise revenues of $5 each month until the end of the contract. Now, if you bought twelve milkshakes at once and took them home, then the seller would have provided the goods and therefore would recognise the $60 revenue. Getting these things mixed up can appear misleading so ensure you’re clear with investors. Bookings = contract value. Revenue = money for the service or product that has been provided. Gross Merchandise Value or Revenue? Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) is the total value of the transactions going across a marketplace. Revenue in this case is the amount that the company takes from a transaction - the commission, either flat-rate or percentage. If I have a marketplace for bringing together buyers and sellers of shoes, and 100 pairs of shoes are sold at $25 each then the GMV is $2,500 (sales price x number of sales). If in the next month the 200 pairs of shoes are sold at $25, clearly the GMV is $5,000. GMV therefore shows the activity of the marketplace and helps investors understand the market size. If the company charges 10% on transactions, then revenue would be $250 and then $500 on the above examples. GMV is not revenue, it’s about the market not the money your company is making. Revenue is the amount your company makes by providing a service - in this example the service is bringing together a buyer and seller and facilitating a transaction. Monthly Figures or Cumulative Figures? If you sell three items in month one, two in month two and one item in month three, your sales are clearly declining, but if you show a cumulative chart - it’ll still show an increase, from 3 to 5 and then 6. Investors do not like cumulative charts because they are misleading. We want to see your monthly users / sales increasing and at what rate. Therefore, while it may be tempting to use cumulative charts, don’t. Show your monthly activity and your month on month (MoM) growth. If your product is right and you’re reaching your customers, your users / sales should be increasing every month. If they aren’t you need to question why; and then make changes that drive growth. Once you have some solid month on month growth, then you have an interesting chart to show investors. Downloads or Active Users?

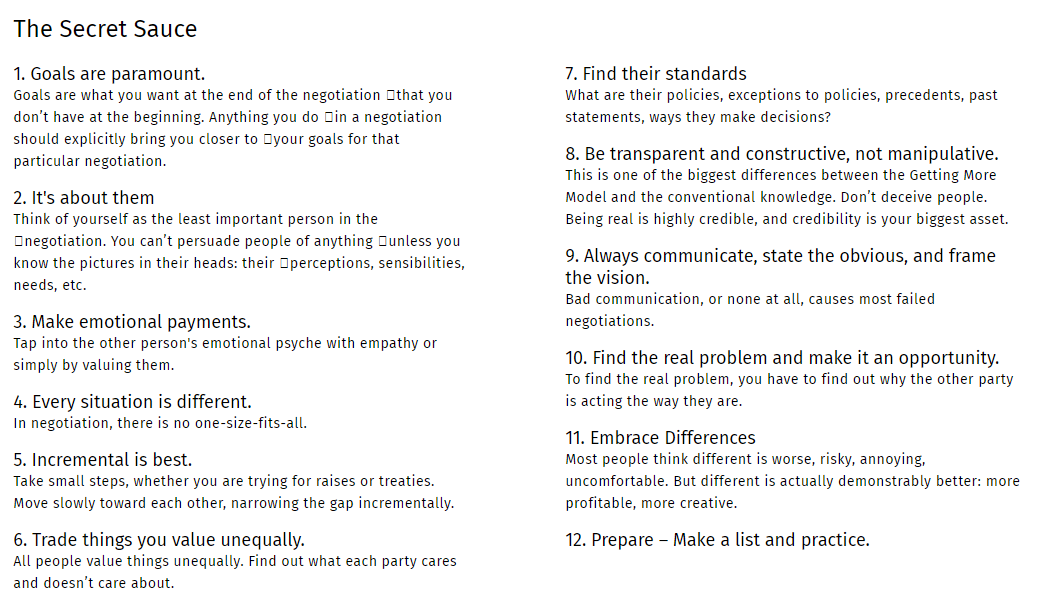

Downloads is the number of people who have downloaded your app, while active users is those users that are still using it. Active users would tend to be quarterly, monthly, weekly or daily - it depends on what your app / service is. Pick one that works and use it. You might have 500,000 downloads, but active users is where the value lies as these are the people actually engaging with your product. We would recommend breaking your active users into groups (i.e. paying, not paying) to help show if your business is managing to increase users who are paying for your services. Also consider if your active users are carrying out behaviours which you want to tell potential investors - such as recommending new users, providing positive feedback or enquiring for additional services. Operating Expense or Costs of Goods Sold? Costs of Goods Sold (COGS) relates to the costs required to produce a product. Operating Expenses are expenses that are not directly related to producing a product. Let’s say I sell a banana milkshake for $5; I paid a total of $2 for the milk, ice cream and bananas so my COGS were $2 (or 40%). The milkshake was made by my staff member who receives a salary, in my cafe where I pay rent using electricity which I pay a utility bill for; each of these items is an operating expense. With a software-as-a-service (SaaS) business, COGS tend to refer to the costs involved with providing the software: hosting fees, third-party products involved in delivery, and employee costs for keeping things running. It’s worth being clear what you’re including in SaaS COGS as some investors may have slightly different interpretations. Why is it important to define COGS properly? Because revenue minus COGS is equal to gross margin; and dividing gross margin by sales revenue gives you gross margin percent which tells you (and investors) how much the company retains from every dollar (or Kyat) sold. Update 9th July 2019: Comment from Sam Glatman, Founder of "Zingo" a startup in Myanmar providing oral care products for betel nut chewers: The metrics that matter article is great and raises an issue that we have been working on internally recently. In our case, we have been differentiating between “sell in” and “sell out”. “Sell in” is a sale on credit to a distributor. “Sell out” is a sale either by us directly or by a distributor to a betel vendor who pays hard cash. We realised that while “sell in” is where our top line revenues come from, the only relevant metric for us is “sell out” because it’s leads to hard cash, and demonstrates real consumer demand. For us (and many start ups), cashflow is a far more relevant success (& survival) metric than P&L, and top line revenues are not as indicative of cashflow as might be expected. Pay Rises and Hostage Situations When did you last negotiate? Probably, it was sooner that you realise. Negotiation isn’t all pay rises and hostage situations, it’s the process of agreeing on an outcome. If you want to leave work early today, you might offer to stay an hour later tomorrow. If you picked what to eat last night, perhaps you told your friend / partner that they could pick next time or explained that you knew the best place to go. These are negotiations in our daily lives. We negotiate every day to some degree, but if we don’t even realise we’re doing it, how do we know if we’re getting enough in the agreement? In his book, Getting More, Stuart Diamond teaches how with some simple core principles it’s possible to become more effective negotiators, both at work and in our day-to-day lives. Diamond is an American Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, professor, attorney, entrepreneur, and author who has taught negotiation for more than 20 years. But, he claims, the lessons in his book can be implemented by anyone. Sounds too good to be true? I gave Diamond’s lessons a try and got a big discount at a local gym - not life-changing, but many little discounts add up. On a more relevant topic, investors and founders will hold hundreds of negotiations between one another. Of course, valuation is often a negotiation, but think about term sheets, CEO salary, budgets, future capital raises or even small things like requesting support, asking for introductions or agreeing on where your board meeting will be held. Diamond is clear in his book: if both parties understand negotiation, both can come out with more. Diamond's 12 Strategies Don't be Hard, be Smart

How can both parties get more? It depends how you define “more”. One thing Diamond teaches is being very clear about what you and the other party want. First, ask three questions: What are my goals? Who are “they”? What will it take to persuade them? Next, ask yourself these same questions for the other person (or persons). Then, try to trade things of unequal value. I wanted to go to the gym in the morning, not the evening; mornings are not busy at the gym so I asked if I could have an off-peak discount. I traded “peak hours” which had zero value to me, while the gym could still improve their income by selling a product of lesser value to them “off-peak hours”. All that was necessary was understanding what each party wanted. I didn’t want “gym membership” but rather “access to the gym early in the morning.”. If you’re raising capital, do you want “$100,000” or “funds to help you scale”? Does the investor want “as much equity as possible” or “equity enough to balance their risk”? If it’s about balancing risk, how else could you reassure the investor? The key is once you have a clear picture in your head of what you want, you need to get that picture into the head of the other person. To do this, Diamond recommends role playing the negotiation - taking the role of the other person. Think about what they want, how they would respond and have a friend help you go through the motions. If you can understand the picture in the other person’s head, you’ll have more chance of discovering how to show them the picture in yours. Borrow the Book from EME There’s a lot more to discover in Diamond’s book - if you’re interested, we have a copy at EME we’d gladly lend to you. Diamond can be a bit self-congratulatory, but it's worth persevering through at least the first half of the book. Before we finish, let me leave you with some key points that echo throughout his book:

|

Categories

All

Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed