|

Covid-19 has changed how people think about investing, at least for now. Funds were quick to offer advice that more or less said: spend less money while making the same money or more money. Which raises the question, what were companies doing beforehand? Of course the first response is that growth costs money and startups should be growing exponentially. But there’s a wider observation here which the market is closer to accepting: supporting growth at any cost and really nasty unit economics, probably isn’t always the smartest investment you can make.

What happens next? This is the question on everyone’s mind. Do we see a L-U-V? For the uninitiated, these letters indicate the possible shapes of economic recession and recovery and - spoiler alert - no one knows which it’ll be. “V” sees the economy bouncing back, “U” a slower recovery and “L” a very long / slow one. The most common sense analysis that your writer has come across suggests that the recovery will be sector-specific; regardless of the overall shape, the shape for different sectors will differ. As investors, that means finding the sectors that are going to look more like “V” than “L”. Right about now readers of this post are probably thinking of delivery businesses as hot new sectors, but we’d caution that such business has seen an increase in demand (not a decrease as many sectors) and this demand may lull as restaurants and shops open again. And so we have to think a bit harder. Unfortunately, we’re not about to reveal all the sectors that will bounce back with a vengeance, because we don’t know. We do believe that more people in Myanmar will continue shopping online as they’ve been forced to experience its convenience, and we expect that this increase of demand will help buoy eCommerce in general. Other services going online may also fare better than before Covid-19, though not all. Will people buy more cars to avoid public transport? Probably those who can afford to will, but private vs public transport is a very income-driven choice in emerging markets. People are not suddenly better off. In fact, the economic impacts are going to hit the broad majority of people, just think about key affected sectors: tourism, apparel, agriculture, fisheries, F&B. That’s not part of the economy, that’s the economy. Meanwhile, investors have dry powder (i.e. money to invest) and will be supporting their existing portfolios, but also continuing to make new investments. With that acknowledged, let’s say for the sake of argument that whatever happens next there’ll be some new investments being made. Here enters the role of the Schumpeterian entrepreneur: the trail blazer who spots opportunities, takes risks and creates value which disrupts the market. Heed this: consumers and businesses are going to be looking for innovations that help them through the more challenging times ahead. Innovations are not inventions. Invention is making a light bulb, innovation is everyone using light bulbs in their homes; innovation is the commercialisation of invention. Some countries are great at invention and innovation, others less so. But, innovation can be imported from abroad (just look at China’s growth since the 90s). We’ve seen successful and unsuccessful attempts at startups using business models already popular abroad to launch products and services in Myanmar. Obviously, not all ideas that work elsewhere will work here. But many will. We’re not suggesting for a moment that starting a business from scratch and making it a success is easy just because the idea works somewhere else. We know that it isn’t. What we are saying is that there are tough times ahead and entrepreneurship is going to be a key component in prospering through them. And so, to anyone reading this who has recently started a new venture, we commend you. Entrepreneurs break boundaries because they take risks, and that takes guts. Got an idea? Innovation requires executing on ideas; “Vision without execution is hallucination”, meaning that it's putting the idea into action that’s the hardest part. We can all dream of flying cars, after all. To help guide your idea, we’ve developed a pitch deck template for you which asks you to answer certain questions. Feel free to use this next time you’re pitching. And, if you’d like our feedback, send it over and we’ll let you know what we think! [email protected]. Above: John Lim, ARA Asset Management (photo credit: DealStreetAsia) We packed our bags and headed to clean and pristine Singapore to meet with and hear from leading regional investors and founders at the DealstreetAsia™ PE-VC Summit 2019. Arriving at the conference, we quickly noticed that we were in a very select minority of investors from Myanmar – an indication of the country’s early frontier status. People were curious about Myanmar and excited to hear about our work and our incredible portfolio companies. Over copious coffees and one or two beers, we shared, listened and learnt. This short post summarises some of the key insights from the presentations, conversations and gentle persuasions of the event. Underlying each of the following points are three core values we observed from the summit: know your customers and put them first, work hard and smart, and lastly, find an investor you can build a relationship with.

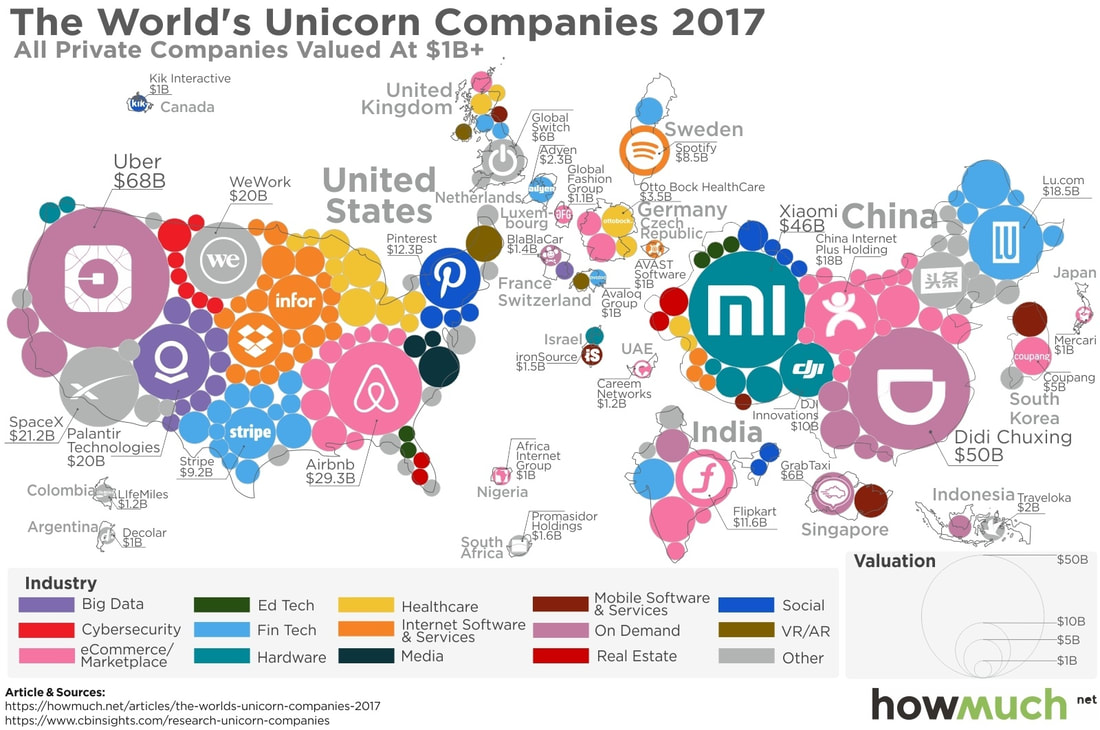

Lesson 1: Don’t Try to Make Money One thing we weren’t necessarily expecting to hear at an event where the total assets under management of all parties was over $100bn was “don’t try to make money”. However, founder and CEO of Deskera, Shashank Dixit told a roomful of investors and founders to focus on building great companies that serve customers and let the money follow. We see value in this sentiment: startups need to deliver outstanding value to their customers - with scaleable unit economics - and if they succeed then exponential growth will happen. Once your product or service is too good to be without, you’re set on a course for scale; so long as you scale with the right unit economics, the riches will come. Focussing on making money, on the other hand, isn’t putting your customer first and introduces short-termism that could prevent you from building something great. Indeed, EME’s permanent capital approach (rather than a fund with an exit deadline), means that we can work with entrepreneurs to build great companies and take a long-term view with founders. Lesson 2: The Importance of Trust One of our favourite one-on-one on-stage discussions was the interview with John Lim. Son of a schoolteacher, John Lim is the cofounder of ARA Asset Management which has $58 billion in assets under management. Lim spoke about how crucial trust was in long-term business relationships, citing that he had a long-term multi-billion-dollar arrangement based purely on a handshake. This introduces an interesting thought experiment: would you trust your partner to honour the agreement purely on a handshake? Often the answer is “no”, which is why we have contracts and may be fine for short-term transactions. When it comes to investing, though, we want to be able to treat contracts as a formality, understanding that there is an enduring trust between us and those we invest in. This approach forces transparency, accountability and integrity on all parties, which can only be a good thing. Keep this in mind next time you review a term sheet. Lesson 3: 007, not James Bond China’s growth has been built in part upon the 996 model: people working diligently from 9am until 9pm, six days a week. This might feel quite gruelling for the employed, but for founders John Lim says they should be following the 007 model. 007, in case you haven’t worked it out yet, is 12am-12am, seven days a week (i.e. 24/7). Of course, even Elon Musk sleeps (a little), but the sentiment is that to build something great, founders must commit and put in the work. In fact, when asked about the secret sauce for founders, Lim offered: there’s no secret sauce for startups or CEOs. They must be passionate, know their stuff, be patient and work hard. He added: “Don’t open a restaurant because you love food. If you want to start a restaurant, work in one, understand the customers, the supply chain and the problems; after a couple of years, only then might you be ready.” Lesson 4: Vision Without Execution is Hallucination Southeast Asia is creating more and more unicorns (startups valued >$1bn), but these companies are coming from great execution more than they are fresh innovation. Given that SEA is quickly developing, there is significant scope to take models born in Silicon Valley or elsewhere and transplant them into these markets. Investors and founders at the event agreed: SEA is an execution game. This is as true in Myanmar as anywhere else and perhaps even more so given the country’s only very recent emergence from military rule. In Myanmar, there are plenty of opportunities to disrupt traditional business with nimble ideas from other markets. How to execute? This requires excellent founders who can deliver on their strategies, who can roll up their sleeves and make things happen, who have a drive and determination to ensure dreams become reality. Decisions might happen in the boardroom, but the real work takes place on the ground. Lesson 5: The days of investing and taking a backseat are over Investing in startups is becoming increasingly competitive. With a challenging global economy and more funds available for a greater array of startups, investors are reflecting on the role they play. Across many conversations and panels, a theme emerged that simply betting on a founder and walking away, hoping they succeed, is a dying strategy. Founders expect their investors to become partners, not just cheque books. In Myanmar, there is less capital than most markets in SEA but this doesn’t mean founders need to be happy just accepting cash. In fact, EME’s model is based on investing capital and significant time into our portfolio companies – helping them to overcome their challenges and find a pathway to scale. Agree, disagree or have additional lessons to share? Drop us a line at [email protected]! Above: the EME team (after we escaped) Last Friday the EME team headed out to Xcape Squad, one of Yangon’s escape room venues (they’re not sponsoring this blog). After we escaped, we reflected on some lessons that also apply to founders and startup teams. For those that aren’t familiar with the escape room format: a small group of people is locked inside a room and must solve several clues to unlock the door all within an hour. The time pressure and limited information forces a need for communication and collaboration, something that startups will appreciate as they face pressure to grow / raise before the money runs out.

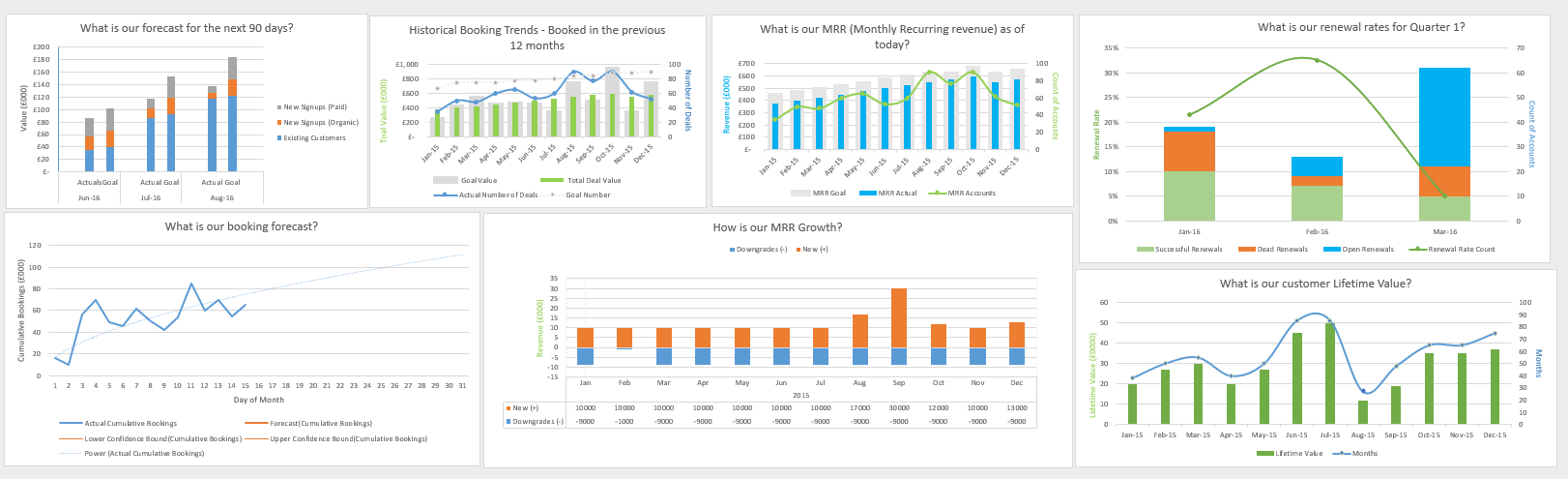

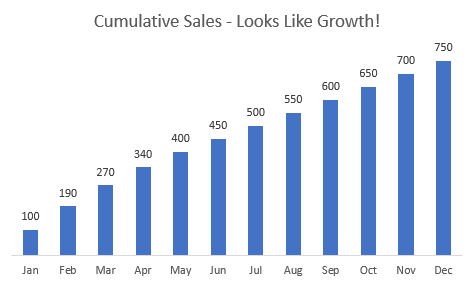

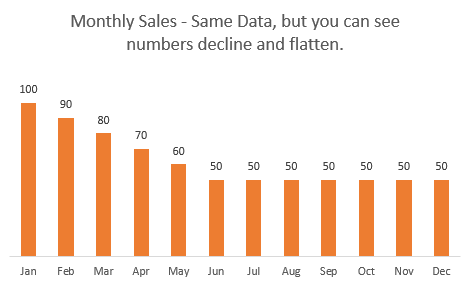

Here’s what we learnt: #1: Map Your Surroundings Before starting off in the wrong direction, it’s important to understand your surroundings – your market, competition, customers. You might have what feels like a great idea, but until you’ve spent time checking your assumptions, your great idea is unqualified. When we got into the room, we found several long sticks and immediately started seeing where they would fit – but there was a very big clue that we missed for a while because we hadn’t properly assessed our surroundings. Startups sometimes make this same mistake by missing crucial elements that affect the viability of their model. To avoid this, ensure you’re consciously aware of who your company is serving, why it’s serving them and why they would use your service over any other. #2 Don’t Forget Fundamentals Escape rooms force you to solve clues in order, but before we learnt this, we were flailing around trying to solve several clues at once. Startups should be fast and nimble, able to race ahead. But, even the fastest startup needs some key fundamentals in place and missing these is going to cause severe growing pains later down the line. Yes, we’re talking about clear financial reporting, sales tracking, customer management, staff management, etc. It’s important that there are at least basic and functional systems in place as a foundation to grow upon. Whether its simple spreadsheets or free / freemium software, it’s also important to keep track of what you’re doing. How else are you going to show your achievements? How can you ensure you’re making the right pivot without a clear record of what’s happened so far? #3 Have a Plan and Embrace Horizontal Structures When there’s just three of you, it’s a good idea to ensure that anyone with a smart idea can bring it to the fore. This is as true for the escape room as it is for business, and it’s not just limited to three people. In a startup you’ll have a small number of people (at least to begin with) with different skillsets and in different positions. Firstly, everyone should understand what the company is working towards and how to get there. Second, this plan should be changeable if new information is presented – by staff at any level. Sales people know why customers are or aren’t buying, the customer service team knows what customers like or dislike about your products / services, the marketing team knows how to advertise key messages, and so on. While the CEO should be plugged into these things, it’s also the CEO’s role to ensure that all staff have a voice and can contribute to achieving or altering company goals. #4 Get Advice To quote one famous sports coach, “In life, you need many more things than talent. Things like good advice and common sense”. We had three opportunities to get help with clues and we used every one. Getting hints to solve clues helped us move faster when we hit a roadblock. This is the role that mentors, advisors and board members (we’ll call them all mentors for now) should play for startups. It’s the founder(s)’ role to find good mentors and “good” is going to be different depending on the startup need or company stage: it could be someone from the industry that brings connections and technical knowhow, or a venture capitalist with ability to help raise additional funding, or simply someone with experience to help bounce ideas off of. #5 Celebrate Wins, But Keep Going When we solved a clue, we high-fived and patted ourselves on the back but as we were against the clock, we soon moved on. Startups should do the same. It’s going to be hard to scale your business and all the odds are against you, so celebrate wins even when they’re small. Celebrate big wins too but – and this especially relates to what you might see as big wins – celebrate then keep going. It is not the role of the startup to get comfortable. Comfort is for the slow-moving corporates. If you’ve raised money, it’s time to work double as hard to ensure you deliver to investors and have them re-invest or help you find investment to scale further. There might not be a clock ticking down to zero in your office, but be sure: you are against the clock, if you don’t move fast enough then someone else will. We’ve met more than 150 startups in Yangon and Mandalay and we continue to meet more every week as we seek the most promising early-stage companies in Myanmar. Over the course of these meetings, we’ve seen and heard some excellent pitches as well as some more confusing ones. We’ve noticed on a few occasions some confusion over certain terms when it comes to startup company metrics. Therefore, we thought it would be useful to clear up some terminology on business and finance metrics for startups. This isn’t a list of the only metrics you should be measuring. It is a list of things we know people get wrong sometimes. It’s also a list of the metrics that we like to see at first glance. These metrics tell us about the company and market potential and provide enough information to get us interested to learn more (assuming the numbers are good!). If anything remains unclear after reading, or prompts a question, contact us at [email protected]. Revenue or Bookings? Revenue is recognised once a service or product has been provided. Bookings is the value of the contract between the company and the customer. Let’s say you subscribe to receive a monthly milkshake for $5/month, you sign a twelve-month subscription for $60. The $60 represents the bookings for the milkshake seller. The milkshake sellers will then recognise revenues of $5 each month until the end of the contract. Now, if you bought twelve milkshakes at once and took them home, then the seller would have provided the goods and therefore would recognise the $60 revenue. Getting these things mixed up can appear misleading so ensure you’re clear with investors. Bookings = contract value. Revenue = money for the service or product that has been provided. Gross Merchandise Value or Revenue? Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) is the total value of the transactions going across a marketplace. Revenue in this case is the amount that the company takes from a transaction - the commission, either flat-rate or percentage. If I have a marketplace for bringing together buyers and sellers of shoes, and 100 pairs of shoes are sold at $25 each then the GMV is $2,500 (sales price x number of sales). If in the next month the 200 pairs of shoes are sold at $25, clearly the GMV is $5,000. GMV therefore shows the activity of the marketplace and helps investors understand the market size. If the company charges 10% on transactions, then revenue would be $250 and then $500 on the above examples. GMV is not revenue, it’s about the market not the money your company is making. Revenue is the amount your company makes by providing a service - in this example the service is bringing together a buyer and seller and facilitating a transaction. Monthly Figures or Cumulative Figures? If you sell three items in month one, two in month two and one item in month three, your sales are clearly declining, but if you show a cumulative chart - it’ll still show an increase, from 3 to 5 and then 6. Investors do not like cumulative charts because they are misleading. We want to see your monthly users / sales increasing and at what rate. Therefore, while it may be tempting to use cumulative charts, don’t. Show your monthly activity and your month on month (MoM) growth. If your product is right and you’re reaching your customers, your users / sales should be increasing every month. If they aren’t you need to question why; and then make changes that drive growth. Once you have some solid month on month growth, then you have an interesting chart to show investors. Downloads or Active Users?

Downloads is the number of people who have downloaded your app, while active users is those users that are still using it. Active users would tend to be quarterly, monthly, weekly or daily - it depends on what your app / service is. Pick one that works and use it. You might have 500,000 downloads, but active users is where the value lies as these are the people actually engaging with your product. We would recommend breaking your active users into groups (i.e. paying, not paying) to help show if your business is managing to increase users who are paying for your services. Also consider if your active users are carrying out behaviours which you want to tell potential investors - such as recommending new users, providing positive feedback or enquiring for additional services. Operating Expense or Costs of Goods Sold? Costs of Goods Sold (COGS) relates to the costs required to produce a product. Operating Expenses are expenses that are not directly related to producing a product. Let’s say I sell a banana milkshake for $5; I paid a total of $2 for the milk, ice cream and bananas so my COGS were $2 (or 40%). The milkshake was made by my staff member who receives a salary, in my cafe where I pay rent using electricity which I pay a utility bill for; each of these items is an operating expense. With a software-as-a-service (SaaS) business, COGS tend to refer to the costs involved with providing the software: hosting fees, third-party products involved in delivery, and employee costs for keeping things running. It’s worth being clear what you’re including in SaaS COGS as some investors may have slightly different interpretations. Why is it important to define COGS properly? Because revenue minus COGS is equal to gross margin; and dividing gross margin by sales revenue gives you gross margin percent which tells you (and investors) how much the company retains from every dollar (or Kyat) sold. Update 9th July 2019: Comment from Sam Glatman, Founder of "Zingo" a startup in Myanmar providing oral care products for betel nut chewers: The metrics that matter article is great and raises an issue that we have been working on internally recently. In our case, we have been differentiating between “sell in” and “sell out”. “Sell in” is a sale on credit to a distributor. “Sell out” is a sale either by us directly or by a distributor to a betel vendor who pays hard cash. We realised that while “sell in” is where our top line revenues come from, the only relevant metric for us is “sell out” because it’s leads to hard cash, and demonstrates real consumer demand. For us (and many start ups), cashflow is a far more relevant success (& survival) metric than P&L, and top line revenues are not as indicative of cashflow as might be expected. Following on from our previous post on startup ideas in Myanmar, we’re releasing a second list. This list focuses on more technology-intensive, speculative ideas, particularly for the B2B sector. B2B startups typically face higher barriers to entry than B2C ones, but can be rewarded with stickier customers. Businesses aren’t easy to win and it can take months to get one client, but once onboard they tend to need a reason to switch provider, rather than to stay. Consumers, on the other hand find it much easier to try new solutions and are therefore often harder to keep hold of. In neighbouring India, there has been a huge rise in B2B startups, a lot of which have focussed on enterprise software, such as Freshworks which last year made unicorn status when it raised $100m at a $1.5bn valuation. Myanmar is still a way from seeing its first unicorn, as we discussed in an earlier blog, but we’re definitely seeing innovation in the B2B space - such as Mote Poh, which is redefining ways in which companies recognise and reward their staff. So without further ado, here are our top five speculative B2B tech startup ideas. Same caveat as last time we wrote one of these posts: we haven’t tested or researched these ideas beyond lunch chats and a cursory Google, so try them at your own risk (but if you do try any of them, tell us!).

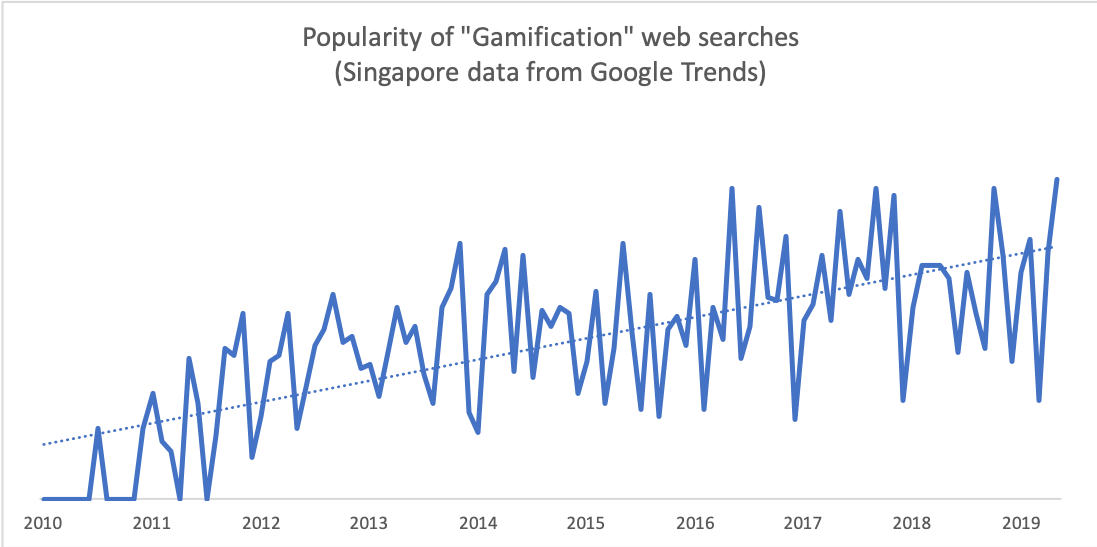

Think we missed something, or our ideas are genius, or completely mad? Write us at [email protected] and tell us why. The Innovation Blind Spot – Why we back the wrong ideas and what to do about it By Ross Baird In recent years, Ross Baird has built quite the reputation for himself. Entrepreneur, investor and now author. In 2009 Baird founded Village Capital, a VC with a unique peer-selection approach, and has since worked with hundreds of entrepreneurs and investors in more than fifty countries, including EME in Myanmar. The hypothesis of his book is that innovation today suffers from three major blind spots – blind spots that negatively affect how we do business, innovate and invest. The first blind spots has to do with how we, as investors, choose new ideas; the second with where we find new ideas; and the third with why – why we invest in new ideas to begin with. These blind spots result in investors overlooking untapped companies, untapped markets and untapped industries. How we invest: One size does not fit all. Innovation breaks moulds, it doesn’t fit them. Baird urges investors to look beyond traditional ways of identifying and selecting startups. Investors rarely make decisions about their next investment at a pitch event. Let’s face it, people who are looking for money are going to tell the people with money what they want to hear, and most investors know that. And not all great founders are pitch wizards. This is one reason EME uses an adaptation of Village Capital’s VIRAL scorecard (see our recent blog) to give founder and investor the chance to have an in-depth discussion. Also, while many VCs prefer to hear about companies through their networks and are closed off to enquiry, our door is open and we’re very happy to meet and discuss with founders who reach out to us. Baird pushes investors to consider their ecosystem. Myanmar isn’t Silicon Valley. Spray and pray (making lots of investments, hoping one or two make it big) doesn’t fit the same metrics here as there and expecting entrepreneurs to model themselves on Brian Chesky (Airbnb CEO) is pretty pointless. The innate diversity of Myanmar forces us to think outside the box, playing to the strengths and uniqueness of individuals, companies and new ideas. True innovation, not copy-paste from outside, takes time and committed investors. Where we invest: looking beyond (a) location. Fun fact: in US, more than 75% of startup investments flows to only three States – California, New York and Massachusetts – the Big Three. Baird points out that, similar to patterns known from real estate, market frenzies over specific locations can cause prices to rise rapidly, and force investors to pay a premium, for no other apparent reason than location. Does this lead to a location price premium for startups? The Myanmar Times recently wrote that Myanmar had a burgeoning entrepreneurial ecosystem. But, while the ecosystem is certainly developing, it’s a Yangon phenomenon, not Myanmar-wide. Is Myanmar on the path of building a Big One like the US has a Big Three? The laws of supply and demand show us that if demand outgrows supply, prices increase, allowing startups to demand a higher price for equity. On the other hand, if there are a lot of startups looking for funding and the demand is limited, prices decrease. As rational investors, one of the things we fear the most is something called, “irrational exuberance.” Irrational exuberance is, simply put, a state of mania. In the (stock) market, it's when investors are so confident that the price of an asset will keep going up, that they lose sight of its underlying value. Investors egg each other on and greedy for profits overlook deteriorating economic fundamentals. Baird urges us to search out opportunities where others are not looking, targeting industries ripe for disruption, and where irrational behaviour is nowhere to be seen. Mark Twain summed this up nicely by saying, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect”. Why we invest: between money and meaning. Baird’s investment philosophy is thoroughly rooted in the impact investment tradition, and he is very much a one-pocket thinker. One-pocket thinking recognises that what’s good for society and what’s good for business does not have to be mutually exclusive. The book offers valuable insights into the rise of impact investing, mapping out its development from the start of the micro finance movement to legendary Ben & Jerry’s, and the growing field of large international venture funds devoted to one-pocket thinking. EME is not an impact investor per se, but we do seek out investments that have positive impact. We are positioned in the intersection between money and meaning, strongly committed to Myanmar’s sustainable development. The book is riddled with interesting statistics, and thought-provoking narratives. Did you know that 50 percent of the Fortune 500 in 2000 were no longer on the list 15 years later? And that female founders are more likely to succeed than male founders? Baird is articulate and knowledgeable which makes a strong foundation for a stimulating read. This is a book well worth reading and will perhaps illuminate your very own blind spots. One of EME’s favourite taxi conversations is discussing what startup ideas could work in Myanmar. As investors, we meet with many startups and ecosystem players and have a birds-eye view of what is happening (and not happening) in the startup world. In this post, we’ll be sharing some of the business opportunities we see in the market that we’d love somebody to take a crack at. In our previous post on the Startup Idea Matrix, we talked about how startups succeed by trying out new strategies in new industries. In Myanmar, there are many tried-and-tested startup strategies from abroad which haven’t been implemented here yet. In particular, we see a lot of opportunity in subscription-based models, which are inherently more sustainable than transaction-based models. Mobile payments players like Wave and OKDollar are beginning to find traction, and startups should capitalize on the emerging opportunity for frictionless digital payments.

As a disclaimer, each of our proposed ideas would require a lot of additional market research, brainstorming, product testing etc, and success is definitely not guaranteed. Yet that’s what makes them worth trying! Without further ado, our top startup ideas are:

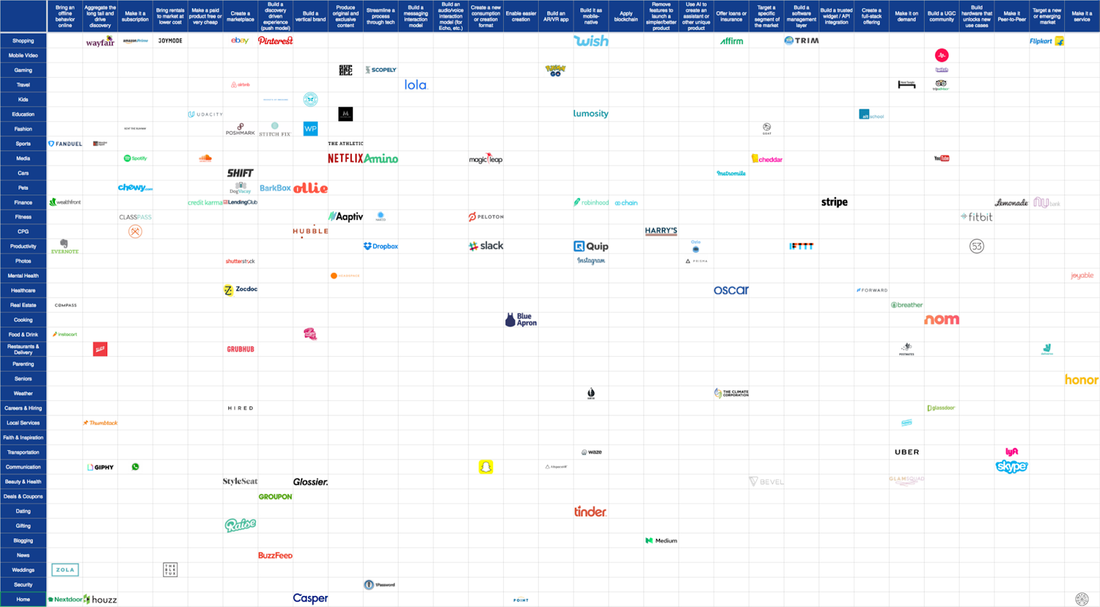

Why do startups exist? Aside from satisfying the financial or social aspirations of the founders, they play a crucial role in the wider economy. Startups innovate, by running semi-scientific experiments to test the effect of new strategies and technologies on problems in the real world. They figure out the right combination of incentives, rules and actors to generate economically valuable activity, and there’s an incredible illustration of this by Eric Stromberg on Medium called the Startup Idea Matrix. In this chart, rows are markets and columns are strategies. Cells contain examples of leading companies that have successfully applied the strategy to the market. For example in the ‘User Generated Content’ column, we have the following market examples:

In the ‘Shopping’ row, we have the following strategy examples:

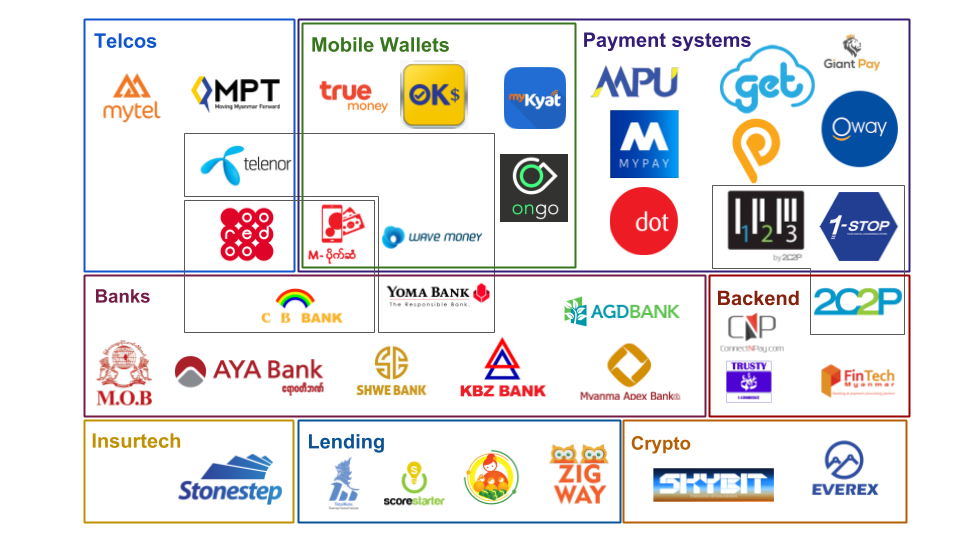

What’s fascinating about the chart is just how much of it is empty. Cells could be empty because that strategy/market combination hasn’t been tried before, or more likely, it hasn’t worked (yet). Note that over 90% of startups fail within 5 years, an incredibly high failure rate which is justified by the huge potential reward for figuring out the right strategy-market combination. Also note that this matrix can and will change over time, as new technologies are invented. For example, the smartphone brought about a wave of new companies and apps that all sought to exploit the new opportunities created by mobile internet-connected devices. Only a small number actually figured out a winning strategy on a global scale - Uber for transportation (in some places), Whatsapp for messaging, Strava for social fitness etc. Even with such terrible odds, systematic experimentation with new strategies and technologies should be the goal of every startup ecosystem, because this produces the economy of tomorrow. We often talk about obliquely about this idea as a venture capital firm, saying “Someone should create a startup to solve X problem in that industry. It’s going to happen sooner or later.” Startups often refer to it when they say they are the “Uber for X”, meaning they are testing the strategy of Uber (on-demand, location-based) on a different market or industry, thereby solving a new problem. Due to barriers of infrastructure and language, a miniature version of this idea matrix could be made for almost every country. There is plenty of low-hanging fruit in Myanmar in terms of proven business models that have worked overseas, and in a future post, we’ll be sharing our top startup ideas that we think could work in Myanmar. We don’t guarantee the success of any of these ideas, but we’d love to chat to anyone attempting them. Who knows, they might just become Myanmar’s first unicorn. Paying for houses and cars in huge pallets of cash is normal in Myanmar right now, but will be almost unimaginable in just a few short years. Financial technology in Myanmar is at a critical inflection point - many players have thrown their hats into the ring and are innovating in order to win customers and digitize a highly cash-based economy. We’ve attempted to map out the current state of the Myanmar fintech landscape below - see how many of the companies you know! As can be seen from the map, payments are especially messy - mobile wallets (Wave, OKDollar etc) are competing with cash acceptance networks (Reddot, 123), banks (AGDPay, KBZPay), card networks (MPU, Visa) and platforms (Oway, Get) in an all-out war to gain traction, although cash is still the main competitor, accounting for over 99% of ecommerce transactions. We expect to see a lot of consolidation in the next 2-5 years, with a digital payment adoption rate that mirrors the trajectories of other countries in the region like Thailand and Indonesia.

One of the major challenges is a lack of financial infrastructure, for example interbank transfers and credit bureaus, although progress is being made on these fronts, aided by new regulation from the government. The fintech ecosystem is evolving rapidly, and overall we think it’s in a healthy state. As adoption rates climb, everyone will reap the benefits of increased convenience and efficiency, driving growth in the economy as a whole. We’re looking forward to seeing how it all plays out. See full list of sectors and players below: Telcos: MPT, Telenor, Ooredoo, MyTel Mobile Wallets: Wave Money, M-Pitesan, True Money, OnGo, OKDollar, MyKyat Payment Systems: MPU, MyPay, Reddot, Get Digital Store, Paypoint, 123, 1stop, Giantpay, Oway Banks: MOB, Aya, CB, Shwe, KBZ, Yoma, MAB, AGD and more Backends: ConnectNPay, 2C2P, Trusty E-commerce, Fintech Myanmar Insurtech: Stonestep Lending: Thitsaworks, Scorestarter, Mother Finance, Zigway Crypto: Skybit, Everex An interesting pattern has cropped up as we comb through our EME database of all the startups and investments in Myanmar from 2012 onwards: we can identify three distinct waves of startups based on time, product and business model. The first wave: fundamentals

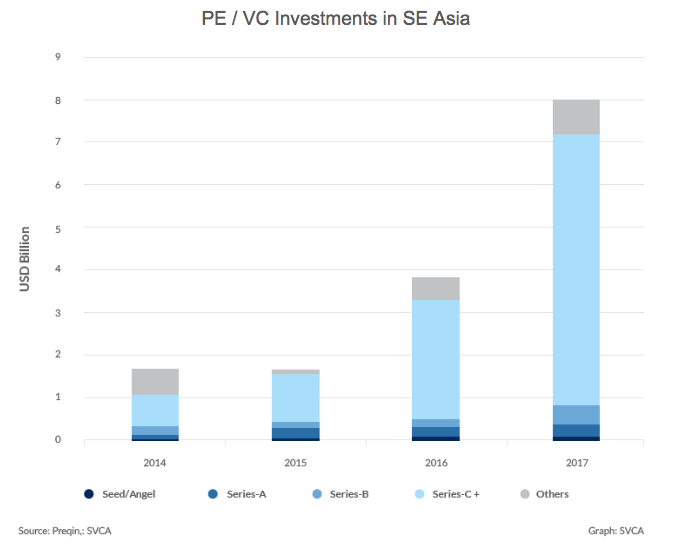

Founded from 2012 to 2014 or so, the first wave of startups were the fundamental consumer internet platforms, mostly online marketplaces for cars, jobs, houses and travel. Often founded by repatriates who had worked in Singapore or the West, these companies included CarsDB, iMyanmarHouse, Oway and MyJobs, as well as more pure-technology companies like Bagan Innovation Technology (Myanmar-language keyboards) and Nexlabs (software development). Rocket Internet entered the market aggressively in 2013 with a stable of platforms including house.com.mm, motors.com.mm, ads.com.mm and more, none of which are still alive today except Shop.com.mm, which is now owned by Alibaba. Honourable mentions go to the nascent social networks and chat apps which didn’t have much of a chance against the blue tide of Facebook that swept the country. Most of the first wave companies are either dead or dominant by now, although new competitors can enter their markets at any point. The second wave: niches From 2015 till 2017, the second-wave was defined by more niche value propositions. There was still a lot of low-hanging fruit to be picked by replicating successful overseas models in more specialized markets. These include companies like Joosk Studio (digital animation and illustration), Bindez (search engine & news aggregator) and Bagan Hub (B2B ecommerce). BODTech also made a round of investments in Flymya (travel), YangonD2D (food delivery), Innoveller (bus ticketing) and more. Also included in the second wave were fintech plays, often by corporates or regional entities. These include large companies like Wave Money, Reddot, Ongo etc, all trying to stake out territory in the digital payments market. Many of these companies are beginning to see real traction, as they carve out their niche in the rapidly growing digital economy. The third wave: experiments We are seeing from now onwards a third wave, defined by greater experimentation, either with business models or with technology. Witness Expa.ai (chatbot builders), RecyGlo (recycling-as-a-service) or Mote Poh (employee rewards coupons). While some of these models have yet to be validated, the ecosystem is in a healthy state as entrepreneurs continue to innovate. Some of this experimentation has been made possible by the entry of institutional investors and accelerators, for example Phandeeyar, whose accelerator program has graduated 11 startups and counting. The incubator / accelerator space is becoming increasingly crowded, with Rockstart Impact, SeedStars, Impact Hub and more beginning to make their presence felt. EME sees opportunities across all three waves of startups. CarsDB, one of our first two investments, is a leading member of the first wave as undisputed #1 in online car classifieds. Our other portfolio company, Joosk Studio is a definite second-wave company - providing a first-of-a-kind product in a specialized field with opportunities for further expansion. We’ll continue to look for companies across this whole spectrum as the Myanmar startup ecosystem develops further. Join the conversation on our Facebook page to let us know your thoughts. We have an office bet going on here at EME. Over lunches at MICT Park and long cab rides to downtown, we discuss the following proposition: Myanmar will create a unicorn (a company with a valuation over $1 billion USD) within the next 5 years. The stakes are a round of beers for us and possibly much higher for the market at large. Disclaimer: we’re not talking about existing companies or prospective investments (that’s a separate bet), so much as the overall trends and market conditions that would allow a unicorn to emerge. As anyone who has stood in line at a Myanmar government office can tell you, there are significant structural challenges for startups to solve. Nevertheless, the population is large, young and increasingly digitally-connected, and as McKinsey suggests, the economy could enjoy years of strong catch-up growth over the next decade in line with other countries in the region like Indonesia and Vietnam. This creates a long-term opportunity for a local tech company to grow into a unicorn. Sector-wise, the startup would probably be in transportation, ecommerce or fintech. All of these sectors have large market sizes, viable business models and can use technology to scale. While other sectors (healthcare, education, logistics etc) also have large potential markets, they are often more challenging to digitize and/or monetize. For funding, this prospective unicorn would probably get seed investment from angels and local funds like EME, then tap regional VC funds and family offices for Series A / Series B. Corporates and later-stage PE/VC investors e.g. Alibaba, Softbank, Sequoia, would fill out the later rounds. Investors are increasingly interested in Southeast Asia and have a lot of unspent capital. As long as this prospective unicorn could demonstrate strong user growth and potentially expansions to other countries in the region, access to finance wouldn’t be an issue. Of course for the purposes of the bet, the potential unicorn would have to avoid getting acquired before reaching that magic $1b valuation. Even after reaching unicorn status, a company may stay private for many years (now often referred to as the Softbank Effect after SoftBank’s $100 billion Vision Fund). Acquisitions by major global platforms seem to be preferred to IPOs at present. Nevertheless, the recent listings of Sea, Razer and Kioson prove that IPOs can be viable for Southeast Asian technology companies.

Overall, we’re very optimistic about Myanmar’s prospects for a unicorn in 5 years. As long as startups continue to work hard, engage users and build products that generate real value, the chances are good that a local player can grow sufficiently fast to achieve unicorn status. It may come as no surprise then, that EME is investing in and supporting early stage tech companies. If you want to join the bet, take our poll on Facebook. See you for beer in 5 years. |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed