|

Following on from our previous post on startup ideas in Myanmar, we’re releasing a second list. This list focuses on more technology-intensive, speculative ideas, particularly for the B2B sector. B2B startups typically face higher barriers to entry than B2C ones, but can be rewarded with stickier customers. Businesses aren’t easy to win and it can take months to get one client, but once onboard they tend to need a reason to switch provider, rather than to stay. Consumers, on the other hand find it much easier to try new solutions and are therefore often harder to keep hold of. In neighbouring India, there has been a huge rise in B2B startups, a lot of which have focussed on enterprise software, such as Freshworks which last year made unicorn status when it raised $100m at a $1.5bn valuation. Myanmar is still a way from seeing its first unicorn, as we discussed in an earlier blog, but we’re definitely seeing innovation in the B2B space - such as Mote Poh, which is redefining ways in which companies recognise and reward their staff. So without further ado, here are our top five speculative B2B tech startup ideas. Same caveat as last time we wrote one of these posts: we haven’t tested or researched these ideas beyond lunch chats and a cursory Google, so try them at your own risk (but if you do try any of them, tell us!).

Think we missed something, or our ideas are genius, or completely mad? Write us at [email protected] and tell us why. The Innovation Blind Spot – Why we back the wrong ideas and what to do about it By Ross Baird In recent years, Ross Baird has built quite the reputation for himself. Entrepreneur, investor and now author. In 2009 Baird founded Village Capital, a VC with a unique peer-selection approach, and has since worked with hundreds of entrepreneurs and investors in more than fifty countries, including EME in Myanmar. The hypothesis of his book is that innovation today suffers from three major blind spots – blind spots that negatively affect how we do business, innovate and invest. The first blind spots has to do with how we, as investors, choose new ideas; the second with where we find new ideas; and the third with why – why we invest in new ideas to begin with. These blind spots result in investors overlooking untapped companies, untapped markets and untapped industries. How we invest: One size does not fit all. Innovation breaks moulds, it doesn’t fit them. Baird urges investors to look beyond traditional ways of identifying and selecting startups. Investors rarely make decisions about their next investment at a pitch event. Let’s face it, people who are looking for money are going to tell the people with money what they want to hear, and most investors know that. And not all great founders are pitch wizards. This is one reason EME uses an adaptation of Village Capital’s VIRAL scorecard (see our recent blog) to give founder and investor the chance to have an in-depth discussion. Also, while many VCs prefer to hear about companies through their networks and are closed off to enquiry, our door is open and we’re very happy to meet and discuss with founders who reach out to us. Baird pushes investors to consider their ecosystem. Myanmar isn’t Silicon Valley. Spray and pray (making lots of investments, hoping one or two make it big) doesn’t fit the same metrics here as there and expecting entrepreneurs to model themselves on Brian Chesky (Airbnb CEO) is pretty pointless. The innate diversity of Myanmar forces us to think outside the box, playing to the strengths and uniqueness of individuals, companies and new ideas. True innovation, not copy-paste from outside, takes time and committed investors. Where we invest: looking beyond (a) location. Fun fact: in US, more than 75% of startup investments flows to only three States – California, New York and Massachusetts – the Big Three. Baird points out that, similar to patterns known from real estate, market frenzies over specific locations can cause prices to rise rapidly, and force investors to pay a premium, for no other apparent reason than location. Does this lead to a location price premium for startups? The Myanmar Times recently wrote that Myanmar had a burgeoning entrepreneurial ecosystem. But, while the ecosystem is certainly developing, it’s a Yangon phenomenon, not Myanmar-wide. Is Myanmar on the path of building a Big One like the US has a Big Three? The laws of supply and demand show us that if demand outgrows supply, prices increase, allowing startups to demand a higher price for equity. On the other hand, if there are a lot of startups looking for funding and the demand is limited, prices decrease. As rational investors, one of the things we fear the most is something called, “irrational exuberance.” Irrational exuberance is, simply put, a state of mania. In the (stock) market, it's when investors are so confident that the price of an asset will keep going up, that they lose sight of its underlying value. Investors egg each other on and greedy for profits overlook deteriorating economic fundamentals. Baird urges us to search out opportunities where others are not looking, targeting industries ripe for disruption, and where irrational behaviour is nowhere to be seen. Mark Twain summed this up nicely by saying, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect”. Why we invest: between money and meaning. Baird’s investment philosophy is thoroughly rooted in the impact investment tradition, and he is very much a one-pocket thinker. One-pocket thinking recognises that what’s good for society and what’s good for business does not have to be mutually exclusive. The book offers valuable insights into the rise of impact investing, mapping out its development from the start of the micro finance movement to legendary Ben & Jerry’s, and the growing field of large international venture funds devoted to one-pocket thinking. EME is not an impact investor per se, but we do seek out investments that have positive impact. We are positioned in the intersection between money and meaning, strongly committed to Myanmar’s sustainable development. The book is riddled with interesting statistics, and thought-provoking narratives. Did you know that 50 percent of the Fortune 500 in 2000 were no longer on the list 15 years later? And that female founders are more likely to succeed than male founders? Baird is articulate and knowledgeable which makes a strong foundation for a stimulating read. This is a book well worth reading and will perhaps illuminate your very own blind spots. We hear hundreds of pitches a year and we’ve realized there are only two elements you really need: a story, and numbers.

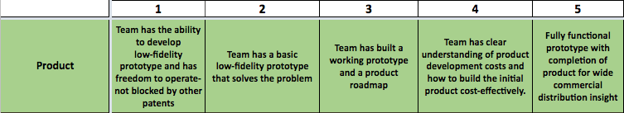

People love stories. They provide meaning to an otherwise disordered and chaotic world. As celebrated author Yuval Harari argues in Sapiens, human civilization developed due to the creation of ‘shared myths’ - stories that allowed large group of humans to cooperate under the banner of a common tribe, religion or civilization. As investors, we’re looking to see if you can tell us a compelling vision for how you want the world to be. If you can convince us, then you can likely convince your future customers and employees about your idea too. Steve Jobs reputedly had such an ability to persuade people that colleagues described it as a ‘reality distortion field’. It’s no coincidence therefore that Magic Leap, a company making next generation augmented-reality hardware, managed to raise billions of dollars before ever releasing a product or making a cent. On the other hand, numbers are super important too. Nobody is going to argue with 10-20% month-on-month growth, and we guarantee that all investors will salivate over a hockeystick- shaped revenue chart, particularly if it stretches back more than 6-12 months. Numbers (particularly revenue, transactions and active users, although the important metric will vary somewhat by industry) prove that you have convinced some people, somewhere out there, to spend some time or money on your product. This means that you are creating value and it’s a necessary condition for a successful idea. Buffer is a good example of a simple idea (social media scheduled posting) with great traction and execution. In this case, the founders managed to tell a compelling story based around how quickly they were growing. Ideally, your numbers and your story back each other up. A word of caution however - don’t try to fake the numbers, and don’t pump up growth artificially by spending huge amounts on marketing. It doesn’t take much business savvy to sell a $10 product for $1, although your numbers will look great for a little while. While these growth-at-all-cost strategies may work for the big American and Chinese startup ecosystems (think of the huge amounts spent on ride hailing and food delivery promotions), they take a huge amount of investor capital and have a very high failure rate. In emerging markets, investors are generally more cautious and want evidence that you are actually creating sustainable value for your users. Check out this excellent gallery from Airtable contains historical examples of pitch decks from successful companies. We particularly liked WeWork, Buzzfeed and Youtube. In these pitch decks, you can just smell the potential sizzling. There’s an energy to them, generated by the combination of compelling stories and early growth that foreshadows their successes to come. All standard pitch deck templates contain a similar set of elements: Problem, Solution, Market, Traction, Team etc. We think these are important, and you should definitely have these elements (check here for our favourite guide ). But more than that, spend time on coming up with a good story. Then generate the numbers to back it up. That’s all there is to it, really. Evaluating early-stage startups as an investor is hard. Giving constructive feedback is even harder, at least if you want to say more than ‘Cool idea’ or ‘You need more traction’. That’s why at EME we use a tool called the VIRAL Scorecard, originally developed by the folks at Village Capital, to be more rigorous in our conversations with startups. Before we dive into how it works, it’s worth emphasizing that this is a discussion tool, not an objective, quantitative measurement of a company’s worth. Data scientists out there may wish it was possible to measure a couple of key indicators, feed them into a model and predict which companies will succeed, but that’s not how early-stage companies work. JFDI, an early-stage VC in Southeast Asia tried to do just that with their Frog Score index, but abandoned it after finding zero correlation between how highly a company scored on their index and how well the company did later on. Instead, the VIRAL Scorecard tries to create a framework for a structured discussion about each aspect of a business. The VIRAL Scorecard describes a number of dimensions of a business including Team, Product, Market etc. Each dimension has 10 stages, with criteria for each stage. Let’s take a look at the first couple of stages in the Product dimension: The scores are cumulative, so if you meet the criteria for stage 4, you should also meet all the previous criteria. It’s important to note that the criteria are somewhat subjective - what is the difference between ‘low-fidelity prototype’, ‘working prototype’ and ‘fully functional prototype’ for example? Here’s how we use the tool when we talk to a startup:

In the meeting, we go through each component of the VIRAL Scorecard, first asking the startup to share their score and reasoning. Then we’ll share our score, and ask follow-up questions. If the scores are similar, great, we’re on the same page. If the scores are very different, that tells us one of two things: EME and the startup has access to different information: As investors, we will know less about the business than the founders, and our scores will reflect that. At an early stage, we probably won’t have seen detailed financial projections or customer feedback. Conversely, sometimes we will know more about an industry and what the competition is doing than the startup. If this is the case, we’ll have a discussion and often revise our scores. EME and the startup have different understandings of the fundamentals of the business: Sometimes startups will try to score themselves as high as possible, in the hope that this will make the company seem more attractive. It’s a reasonable approach when faced with a scorecard, but often has the reverse effect. We want to companies to be aware of their limitations and current state. We’re less interested in the final score and more in constructive dialogue. In this meeting, we’re really trying to get a sense of how the founders think, and how we could work together. It’s a cliche that venture capital investors invest in people rather than companies, but that’s particularly true for early stage startups, which could be several pivots away from their eventual model. This conversation is potentially the beginning of a long-term relationship between the investor and the start-up, and like all relationships, good communication and shared values are essential. These conversations are good for digging deeper into the fundamentals of the business, and often reveal things that we hadn’t even thought of asking about. The VIRAL Scorecard is also helpful in providing concrete points for feedback. Instead of saying things like “You’re too early-stage”, we can say “We’re still unsure about your business model, and we’d like to see some more work done on your unit economics”. We invariably learn a lot from these conversations, and we think they are useful for startups too. At the end of the day, the final score doesn’t really matter - what matters is the quality of the discussion, and the shared understanding that has been created. |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed