|

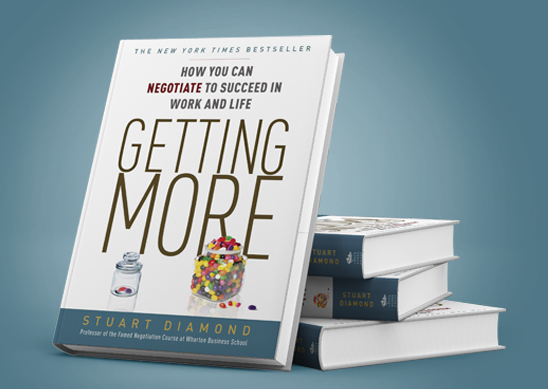

Pay Rises and Hostage Situations When did you last negotiate? Probably, it was sooner that you realise. Negotiation isn’t all pay rises and hostage situations, it’s the process of agreeing on an outcome. If you want to leave work early today, you might offer to stay an hour later tomorrow. If you picked what to eat last night, perhaps you told your friend / partner that they could pick next time or explained that you knew the best place to go. These are negotiations in our daily lives. We negotiate every day to some degree, but if we don’t even realise we’re doing it, how do we know if we’re getting enough in the agreement? In his book, Getting More, Stuart Diamond teaches how with some simple core principles it’s possible to become more effective negotiators, both at work and in our day-to-day lives. Diamond is an American Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, professor, attorney, entrepreneur, and author who has taught negotiation for more than 20 years. But, he claims, the lessons in his book can be implemented by anyone. Sounds too good to be true? I gave Diamond’s lessons a try and got a big discount at a local gym - not life-changing, but many little discounts add up. On a more relevant topic, investors and founders will hold hundreds of negotiations between one another. Of course, valuation is often a negotiation, but think about term sheets, CEO salary, budgets, future capital raises or even small things like requesting support, asking for introductions or agreeing on where your board meeting will be held. Diamond is clear in his book: if both parties understand negotiation, both can come out with more. Diamond's 12 Strategies Don't be Hard, be Smart

How can both parties get more? It depends how you define “more”. One thing Diamond teaches is being very clear about what you and the other party want. First, ask three questions: What are my goals? Who are “they”? What will it take to persuade them? Next, ask yourself these same questions for the other person (or persons). Then, try to trade things of unequal value. I wanted to go to the gym in the morning, not the evening; mornings are not busy at the gym so I asked if I could have an off-peak discount. I traded “peak hours” which had zero value to me, while the gym could still improve their income by selling a product of lesser value to them “off-peak hours”. All that was necessary was understanding what each party wanted. I didn’t want “gym membership” but rather “access to the gym early in the morning.”. If you’re raising capital, do you want “$100,000” or “funds to help you scale”? Does the investor want “as much equity as possible” or “equity enough to balance their risk”? If it’s about balancing risk, how else could you reassure the investor? The key is once you have a clear picture in your head of what you want, you need to get that picture into the head of the other person. To do this, Diamond recommends role playing the negotiation - taking the role of the other person. Think about what they want, how they would respond and have a friend help you go through the motions. If you can understand the picture in the other person’s head, you’ll have more chance of discovering how to show them the picture in yours. Borrow the Book from EME There’s a lot more to discover in Diamond’s book - if you’re interested, we have a copy at EME we’d gladly lend to you. Diamond can be a bit self-congratulatory, but it's worth persevering through at least the first half of the book. Before we finish, let me leave you with some key points that echo throughout his book:

The Innovation Blind Spot – Why we back the wrong ideas and what to do about it By Ross Baird In recent years, Ross Baird has built quite the reputation for himself. Entrepreneur, investor and now author. In 2009 Baird founded Village Capital, a VC with a unique peer-selection approach, and has since worked with hundreds of entrepreneurs and investors in more than fifty countries, including EME in Myanmar. The hypothesis of his book is that innovation today suffers from three major blind spots – blind spots that negatively affect how we do business, innovate and invest. The first blind spots has to do with how we, as investors, choose new ideas; the second with where we find new ideas; and the third with why – why we invest in new ideas to begin with. These blind spots result in investors overlooking untapped companies, untapped markets and untapped industries. How we invest: One size does not fit all. Innovation breaks moulds, it doesn’t fit them. Baird urges investors to look beyond traditional ways of identifying and selecting startups. Investors rarely make decisions about their next investment at a pitch event. Let’s face it, people who are looking for money are going to tell the people with money what they want to hear, and most investors know that. And not all great founders are pitch wizards. This is one reason EME uses an adaptation of Village Capital’s VIRAL scorecard (see our recent blog) to give founder and investor the chance to have an in-depth discussion. Also, while many VCs prefer to hear about companies through their networks and are closed off to enquiry, our door is open and we’re very happy to meet and discuss with founders who reach out to us. Baird pushes investors to consider their ecosystem. Myanmar isn’t Silicon Valley. Spray and pray (making lots of investments, hoping one or two make it big) doesn’t fit the same metrics here as there and expecting entrepreneurs to model themselves on Brian Chesky (Airbnb CEO) is pretty pointless. The innate diversity of Myanmar forces us to think outside the box, playing to the strengths and uniqueness of individuals, companies and new ideas. True innovation, not copy-paste from outside, takes time and committed investors. Where we invest: looking beyond (a) location. Fun fact: in US, more than 75% of startup investments flows to only three States – California, New York and Massachusetts – the Big Three. Baird points out that, similar to patterns known from real estate, market frenzies over specific locations can cause prices to rise rapidly, and force investors to pay a premium, for no other apparent reason than location. Does this lead to a location price premium for startups? The Myanmar Times recently wrote that Myanmar had a burgeoning entrepreneurial ecosystem. But, while the ecosystem is certainly developing, it’s a Yangon phenomenon, not Myanmar-wide. Is Myanmar on the path of building a Big One like the US has a Big Three? The laws of supply and demand show us that if demand outgrows supply, prices increase, allowing startups to demand a higher price for equity. On the other hand, if there are a lot of startups looking for funding and the demand is limited, prices decrease. As rational investors, one of the things we fear the most is something called, “irrational exuberance.” Irrational exuberance is, simply put, a state of mania. In the (stock) market, it's when investors are so confident that the price of an asset will keep going up, that they lose sight of its underlying value. Investors egg each other on and greedy for profits overlook deteriorating economic fundamentals. Baird urges us to search out opportunities where others are not looking, targeting industries ripe for disruption, and where irrational behaviour is nowhere to be seen. Mark Twain summed this up nicely by saying, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect”. Why we invest: between money and meaning. Baird’s investment philosophy is thoroughly rooted in the impact investment tradition, and he is very much a one-pocket thinker. One-pocket thinking recognises that what’s good for society and what’s good for business does not have to be mutually exclusive. The book offers valuable insights into the rise of impact investing, mapping out its development from the start of the micro finance movement to legendary Ben & Jerry’s, and the growing field of large international venture funds devoted to one-pocket thinking. EME is not an impact investor per se, but we do seek out investments that have positive impact. We are positioned in the intersection between money and meaning, strongly committed to Myanmar’s sustainable development. The book is riddled with interesting statistics, and thought-provoking narratives. Did you know that 50 percent of the Fortune 500 in 2000 were no longer on the list 15 years later? And that female founders are more likely to succeed than male founders? Baird is articulate and knowledgeable which makes a strong foundation for a stimulating read. This is a book well worth reading and will perhaps illuminate your very own blind spots. |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed