|

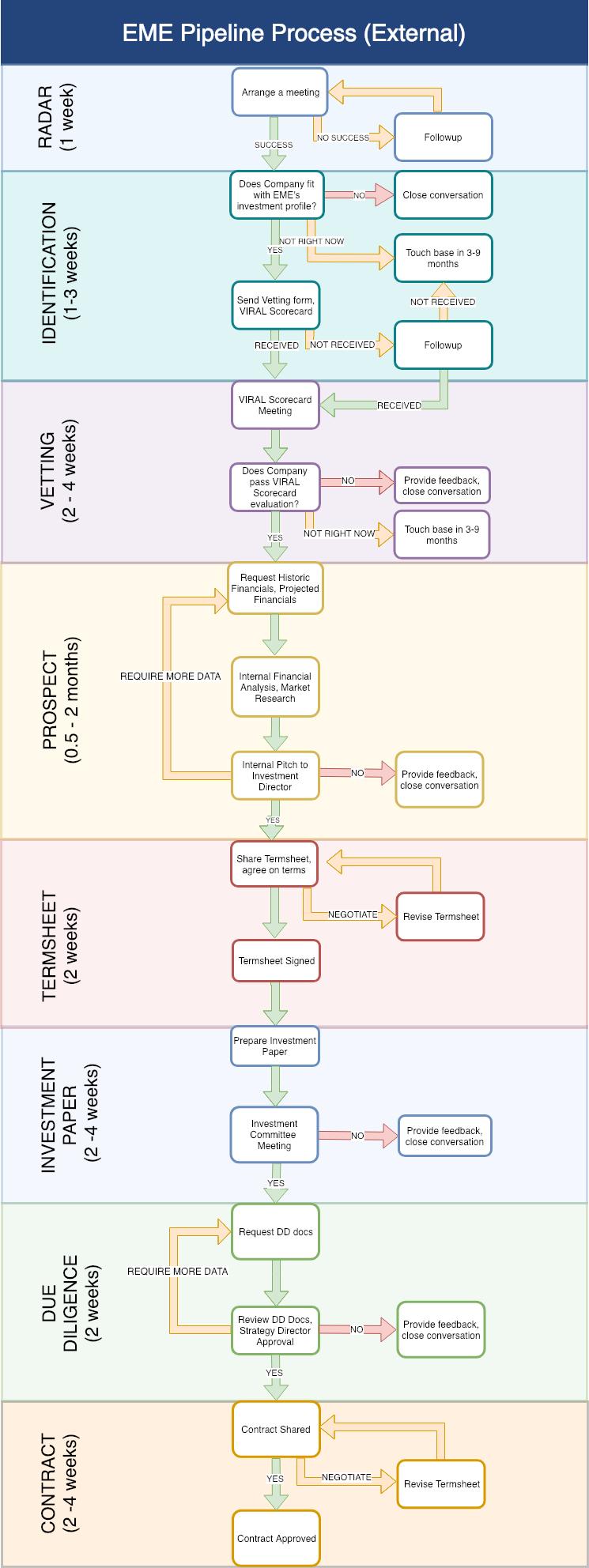

Fundraising for an early-stage startup is hard. Entrepreneurs spend lots of time crafting their message, making decks, networking, pitching and responding to requests for further information, all the while building a product and growing a team. And after several months of hard work, entrepreneurs may end up with nothing for all that effort. On the other side, investing in early-stage startups is also hard. Investors meet hundreds of startups per year, and only a small fraction of them will be alive in 5 years. There is little data and lots of uncertainty, and because VCs have investors too, they look for ways to minimize risk and maximize reward. This combination of incentives often leads to a dysfunctional system, where startups and investors both play shotgun, entering into as many conversations as possible in the hopes that one may succeed. Investors may string startups along for many months without making clear decisions, while startups may start fundraising before they are prepared and ready. The main divide to bridge therefore becomes one of communication and expectations. In this light, we have decided to publish our refreshed pipeline process, which aims to be as transparent and productive as possible. By highlighting all the stages and requirements, as well as the decision points, we hope to contribute some clarity on VC investment (or at least, our approach to VC investment). As can be seen from the chart, the process is reasonably complex - the minimum time for an investment is 3 months, although realistically it can take up to 6 or 8 months. There are also five major decision points, with increasing levels of certainty in later stages of the process. Note that this investment process isn’t for everyone - startups select investors just as much as investors select startups, and if some are put off by the complexity, that’s a good indication that a future relationship wouldn’t have worked out. That said, at all times we take our role in the startup ecosystem seriously and will always coach good startups through the process and provide feedback if and when we stop the process.

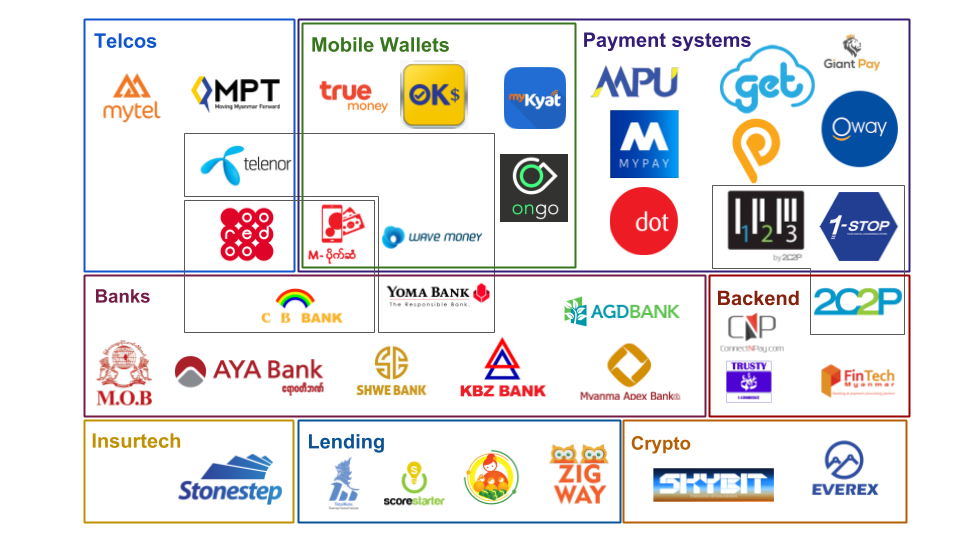

Taking on institutional capital is a big commitment, but we hope our pipeline process is a positive first engagement, and a taste of the value we can bring to our portfolio companies. We are thorough in our selection just as we’re thorough in the support and mentorship we provide our portfolio. Receiving investment from EME is not the end of a process, but the start of a journey of support, guidance and collaboration that is 100% directed at scaling great startups. Paying for houses and cars in huge pallets of cash is normal in Myanmar right now, but will be almost unimaginable in just a few short years. Financial technology in Myanmar is at a critical inflection point - many players have thrown their hats into the ring and are innovating in order to win customers and digitize a highly cash-based economy. We’ve attempted to map out the current state of the Myanmar fintech landscape below - see how many of the companies you know! As can be seen from the map, payments are especially messy - mobile wallets (Wave, OKDollar etc) are competing with cash acceptance networks (Reddot, 123), banks (AGDPay, KBZPay), card networks (MPU, Visa) and platforms (Oway, Get) in an all-out war to gain traction, although cash is still the main competitor, accounting for over 99% of ecommerce transactions. We expect to see a lot of consolidation in the next 2-5 years, with a digital payment adoption rate that mirrors the trajectories of other countries in the region like Thailand and Indonesia.

One of the major challenges is a lack of financial infrastructure, for example interbank transfers and credit bureaus, although progress is being made on these fronts, aided by new regulation from the government. The fintech ecosystem is evolving rapidly, and overall we think it’s in a healthy state. As adoption rates climb, everyone will reap the benefits of increased convenience and efficiency, driving growth in the economy as a whole. We’re looking forward to seeing how it all plays out. See full list of sectors and players below: Telcos: MPT, Telenor, Ooredoo, MyTel Mobile Wallets: Wave Money, M-Pitesan, True Money, OnGo, OKDollar, MyKyat Payment Systems: MPU, MyPay, Reddot, Get Digital Store, Paypoint, 123, 1stop, Giantpay, Oway Banks: MOB, Aya, CB, Shwe, KBZ, Yoma, MAB, AGD and more Backends: ConnectNPay, 2C2P, Trusty E-commerce, Fintech Myanmar Insurtech: Stonestep Lending: Thitsaworks, Scorestarter, Mother Finance, Zigway Crypto: Skybit, Everex Having a Singapore-registered holding company is fast becoming an industry standard among Myanmar and other Southeast Asian startups. At EME for example, we invest from our Singapore holding company into startups’ Singapore registered holding companies because Singapore offers efficient processes for company incorporation, share transfer, as well as tax benefits. However, being registered under the Singapore Company Act comes with certain ongoing responsibilities, namely the filing of the Annual Return on a yearly basis after incorporation. The Annual Return is the electronic filing process to submit required information to Singapore’s Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA). It includes:

Annual General Meeting An AGM must be held once every calendar year. The deadline for an AGM is 15 months from the date of the last AGM. If the company is newly incorporated, it is allowed to hold an AGM within 18 months from the date of the incorporation. Necessary topics for discussion at the Annual General Meeting include:

Up-to-Date Financial Statements At the AGM, financial statements not older than 6 months have to be handed to the Board of Directors. The Financial statement must consist of the following documents:

The company needs to file the Annual Return within one month of holding the AGM. For Annual Filing, the company will usually need to file the financial statements in XBRL (Extensible Business Reporting Language) format, via Bizfile (ACRA's online business reporting system). Since the Myanmar subsidiary company is most likely to be owned 99% by the Singapore holding company (now it can be 100% because the new 2018 Myanmar Companies Law does not require foreign companies in Myanmar to have a local director), the financial reports must be consolidated i.e the Financial Reports of both the Singapore and Myanmar entities. This annual filing process can seem like a daunting process for entrepreneurs. As part of EME's incubation services, we help our portfolio companies to meet the compliances of both Singapore and Myanmar Company Acts. Maintaining regulatory compliance and gtting the books right is a must-do for startups with ambitions to scale. An interesting pattern has cropped up as we comb through our EME database of all the startups and investments in Myanmar from 2012 onwards: we can identify three distinct waves of startups based on time, product and business model. The first wave: fundamentals

Founded from 2012 to 2014 or so, the first wave of startups were the fundamental consumer internet platforms, mostly online marketplaces for cars, jobs, houses and travel. Often founded by repatriates who had worked in Singapore or the West, these companies included CarsDB, iMyanmarHouse, Oway and MyJobs, as well as more pure-technology companies like Bagan Innovation Technology (Myanmar-language keyboards) and Nexlabs (software development). Rocket Internet entered the market aggressively in 2013 with a stable of platforms including house.com.mm, motors.com.mm, ads.com.mm and more, none of which are still alive today except Shop.com.mm, which is now owned by Alibaba. Honourable mentions go to the nascent social networks and chat apps which didn’t have much of a chance against the blue tide of Facebook that swept the country. Most of the first wave companies are either dead or dominant by now, although new competitors can enter their markets at any point. The second wave: niches From 2015 till 2017, the second-wave was defined by more niche value propositions. There was still a lot of low-hanging fruit to be picked by replicating successful overseas models in more specialized markets. These include companies like Joosk Studio (digital animation and illustration), Bindez (search engine & news aggregator) and Bagan Hub (B2B ecommerce). BODTech also made a round of investments in Flymya (travel), YangonD2D (food delivery), Innoveller (bus ticketing) and more. Also included in the second wave were fintech plays, often by corporates or regional entities. These include large companies like Wave Money, Reddot, Ongo etc, all trying to stake out territory in the digital payments market. Many of these companies are beginning to see real traction, as they carve out their niche in the rapidly growing digital economy. The third wave: experiments We are seeing from now onwards a third wave, defined by greater experimentation, either with business models or with technology. Witness Expa.ai (chatbot builders), RecyGlo (recycling-as-a-service) or Mote Poh (employee rewards coupons). While some of these models have yet to be validated, the ecosystem is in a healthy state as entrepreneurs continue to innovate. Some of this experimentation has been made possible by the entry of institutional investors and accelerators, for example Phandeeyar, whose accelerator program has graduated 11 startups and counting. The incubator / accelerator space is becoming increasingly crowded, with Rockstart Impact, SeedStars, Impact Hub and more beginning to make their presence felt. EME sees opportunities across all three waves of startups. CarsDB, one of our first two investments, is a leading member of the first wave as undisputed #1 in online car classifieds. Our other portfolio company, Joosk Studio is a definite second-wave company - providing a first-of-a-kind product in a specialized field with opportunities for further expansion. We’ll continue to look for companies across this whole spectrum as the Myanmar startup ecosystem develops further. Join the conversation on our Facebook page to let us know your thoughts. |

Categories

All

Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed