|

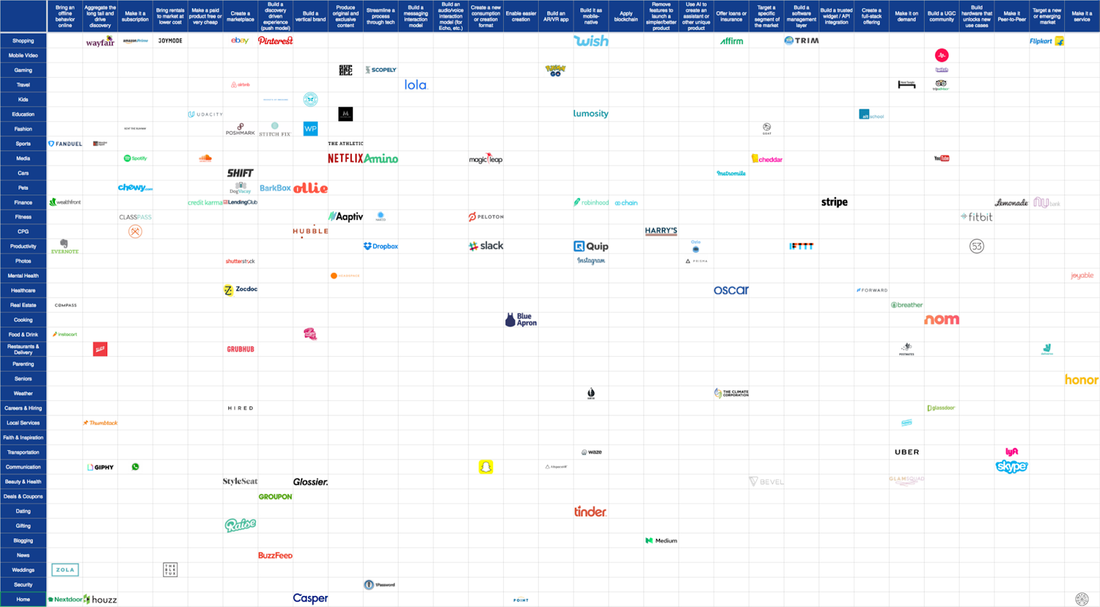

Why do startups exist? Aside from satisfying the financial or social aspirations of the founders, they play a crucial role in the wider economy. Startups innovate, by running semi-scientific experiments to test the effect of new strategies and technologies on problems in the real world. They figure out the right combination of incentives, rules and actors to generate economically valuable activity, and there’s an incredible illustration of this by Eric Stromberg on Medium called the Startup Idea Matrix. In this chart, rows are markets and columns are strategies. Cells contain examples of leading companies that have successfully applied the strategy to the market. For example in the ‘User Generated Content’ column, we have the following market examples:

In the ‘Shopping’ row, we have the following strategy examples:

What’s fascinating about the chart is just how much of it is empty. Cells could be empty because that strategy/market combination hasn’t been tried before, or more likely, it hasn’t worked (yet). Note that over 90% of startups fail within 5 years, an incredibly high failure rate which is justified by the huge potential reward for figuring out the right strategy-market combination. Also note that this matrix can and will change over time, as new technologies are invented. For example, the smartphone brought about a wave of new companies and apps that all sought to exploit the new opportunities created by mobile internet-connected devices. Only a small number actually figured out a winning strategy on a global scale - Uber for transportation (in some places), Whatsapp for messaging, Strava for social fitness etc. Even with such terrible odds, systematic experimentation with new strategies and technologies should be the goal of every startup ecosystem, because this produces the economy of tomorrow. We often talk about obliquely about this idea as a venture capital firm, saying “Someone should create a startup to solve X problem in that industry. It’s going to happen sooner or later.” Startups often refer to it when they say they are the “Uber for X”, meaning they are testing the strategy of Uber (on-demand, location-based) on a different market or industry, thereby solving a new problem. Due to barriers of infrastructure and language, a miniature version of this idea matrix could be made for almost every country. There is plenty of low-hanging fruit in Myanmar in terms of proven business models that have worked overseas, and in a future post, we’ll be sharing our top startup ideas that we think could work in Myanmar. We don’t guarantee the success of any of these ideas, but we’d love to chat to anyone attempting them. Who knows, they might just become Myanmar’s first unicorn. Comments are closed.

|

Categories

All

Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed