|

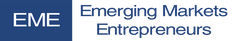

Publishing research is important to shifting the ideas and frameworks that exist within any context, but it's often the role of thinktanks or research agencies. Why then, you might ask, is EME co-publishing this latest report? The answer is simple: across some of our latest investments we've seen a range of businesses putting women at the centre of their business models; from Yangon Broom employing low-income women, Ezay helping rural businesswomen, and Kyarlay whose customers are majority women. Therefore, when we learnt of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation's interest in learning about how entrepreneurship can help close gender gaps in Myanmar, we saw an opportunity to expand our knowledge while studying an ecosystem we know and love. To supplement our knowledge of gender and entrepreneurship, we teamed up with Support Her Enterprise for this study as they work solely with women micro, small and medium enterprise owners to help grow their business. In this report, we survey innovative businesses (typically "startups") with a focus on women and / or girls. These businesses were led by women and / or men, but targeted women either as employees, part of the supply chain or as customers. We also dived deeper into ten case studies with Myanmar women-focussed businesses to learn more about their founding background, approach and outlook as well as their challenges to growth. Finally, we surveyed rural businesswomen to understand the challenges of "necessity-entrepreneurs" and because all women surveyed were buying services from innovative enterprises (indicating that this group of women can afford to pay for services that help them improve their livelihoods - a great indicator that Myanmar is ready to support new and innovative businesses that serve the mass market). Thanks to shared values between the EME and SPF teams, the resulting data of this rural survey is available for all in this online dashboard! The full report is available here in English, and the Executive Summary is available here in English and here in Burmese. Below we've picked out just one of many findings, in no small part because we like bubble charts but also because it raises an important point for young socially focussed startups looking to grow. In the above chart we position companies based on how social or commercial they ranked by our analysis and by what type(s) of funding they had received. The results are quite clear:

1. Bottom Left Red(ish) companies: companies without formal funding tend not to have processes / traction that might help show them as more / less social or commercial. 2. Right Dark Blue: companies who have raised equity tend to be more commercial with a range of how social they are. 3. Middle Light Blue and Middle Orange: Grant-backed companies were more commercial than those without formal funding and in the cases when companies receive grants and equity, they tend to be more social than those only having received equity. What does it all mean? Well: "you are what you eat". Or, put another way: not all money is created equal and any money a startup raises will have different conditions. It's not our role here to comment on which funding is "best" or "most suitable", the answer changes for different companies and may change over the course of a company's lifecycle (and as a VC, EME is probably biased to equity anyway). The orange dots on the chart above may indicate that there is an enabling role in providing grants to startups to help them raise commercial capital. But we also noticed that if a company gets too acquainted with income sources that don't promote sustainability then they may struggle to become lean enough to scale (seems obvious huh?). We at EME believe that scalability is fundamental to impact and commercial growth and it is our role and the role of any ecosystem enabler to help companies work toward sustainable scalability (i.e. positive unit economics). Other findings include: even among the women-focussed businesses surveyed men raised more equity than women; the average costs of a startup is... [see the report!]; and lots of companies like to say they're "social" but only two-thirds actually measured their social results (similarly, many lacked someone in charge of finances so lack of measurement may be more an indicator of overburdened founders than of not caring). Read the full report here. **Note that this blog reflects only the opinions of EME and readers are encouraged to read the Executive Summary and / or full report for the position of all of its authors**

0 Comments

Photo: Broom's team attending a training workshop in 2019

Myanmar’s preeminent on-demand household cleaning business announced in September 2020 that it closed its third round of funding and in doing so, secured its next phase of growth. Yangon Broom will soon be launching its mobile application, as well as creating its own training school to make it easier than ever before to get a high quality cleaning service in Yangon. Following its initial investment from EME Myanmar and Nest Tech VN, Broom has closed Yangon Capital Partners in their latest round. Yangon Broom was founded by co-founders, Kyi Min Han and Kyaw Min Tun who combine experience from recruitment and international quality cleaning, a winning combination for a business that requires hiring and managing hundreds of maids. Together they have grown the company to serve thousands of customers across Yangon, including households, SMEs and schools. Their ethos has always been to put their employees first and this new round will enable them to continue their efforts to train and promote quality within their ranks. With this latest round of growth capital Broom will be finalising their upcoming consumer mobile application, investing further in quality training and laying the foundation for enhanced growth in the coming year ahead. Many cleaning companies have struggled to stay afloat during Covid-19, leaving households and SMEs with limited cleaning options at a time where cleanliness is increasingly important. Yangon Broom’s co-founder and CEO Kyi Min Han said that this investment comes at a time when the company is doing all that it can to support households and businesses to exercise good hygiene and stay safe. Shinsuke Goto, Associate Director of Yangon Capital Partners said, “we were attracted to Yangon Broom because of the trust and reviews of their customers, as well as a clear market trend toward outsourcing domestic cleaning. It’s clear that the co-founders have the right values for this very people-oriented business, putting their maids first and ensuring that they are properly rewarded for their efforts.”. Yangon Capital Partners have made several investments in Myanmar, Konesi, a logistics company and Flexible Pass, a member company. The round was also joined by existing venture capital investors, Emerging Markets Entrepreneurs - Myanmar (EME) and Nest Tech VN who were first-round investors into Yangon Broom and have supported its growth thus far. Hitoshi Ikeya, EME’s Investment Director said “this comes at a good time for Yangon Broom; they’ve proved their position as a market leader in a growth area and we’re pleased to continue to support them as they scale. We’re also very pleased to welcome Yangon Capital Partners as they lead this round”. Image: AdsZay co-founder and Ezay CEO Kyaw Min Swe has developed a network of 1600 and growing rural mom and pop shops which AdsZay is upgrading into advertising and product activation hubs.

EME and Japanese investor Seiji Kurokoshi, together with Ezay, have announced the formation of a new company, AdsZay with a combined six figure investment. AdsZay will leverage the rural shopkeeper network created by Ezay to allow FMCG companies, telco firms and other key players seeking to expand their reach to rural areas. By digitising and delivering stock direct to rural mom and pop stores, Ezay has grown to more than 1,600 active rural retailers since founding its business just six months ago. AdsZay will build a network of dedicated and exclusive ad spaces at each of these stores, paving the way for nationwide growth among brands. Rural mom and pop shops serve anywhere from 50 to 500 households in their respective villages, with customers visiting several times each week. Market research shows that large brands are often poorly represented in rural areas as brand messages are diluted and low prices are the priority of consumers. With AdsZay’s ad display model, shop owners serve as AdsZay’s client’s partners in solidifying brand salience in their respective communities. Data collection, enquiry tracking and an immediate point-of-sale optimizes each ad display unit to ensure the effectiveness of every ad dollar spent. AdsZay’s timing is worth noting. COVID-19 has caused companies to tighten marketing budgets and many households are facing harsher economic conditions. However, now is the time to build and upgrade the AdsZay network, train shopkeepers and fine-tune the AdsZay offer. With unique access to a growing rural network, AdsZay will spend the coming months working closely with its shopkeepers to ensure data accuracy and identify key locations for brand awareness and product activation campaigns. EME’s Portfolio Growth Advisor, Claire Lim, a former Director at Ogilvy, is spearheading the initial stages of AdsZay company development in close partnership with Ezay’s founder, Kyaw Min Swe. After a recent field visit, Claire Lim said, “AdsZay will completely redefine the way that big brands think about these hard-to-reach areas. Very few brands are well represented at the village level and by combining high quality advertising with shop-level data, AdsZay will provide unmatched value”. Seiji Kurokoshi, who recently led a round of investment into Ezay alongside EME, noted Adszay represented the opportunities presented by emerging markets, “Convenience stores in Japan are hubs of information in their communities. We see the same thing in rural areas of Myanmar. AdsZay will upgrade these stores and provide them with new and exciting ways to serve customers while also helping leading brands offer products to new geographies”. Seiji Kurokoshi is a serial angel investor and avid supporter of startups in Japan and abroad, in Japan he owns and runs COEBI Incubation Office, a AAA incubation centre where he supports and invests in social entrepreneurs. His latest investments in Myanmar include into Ezay as well as Myanmar’s leading digital content provider, Bagan Innovation Technology. AdsZay marks the ninth portfolio company for Myanmar-based venture capital company, EME since its founding in October 2018. Other portfolio companies include CarsDB, automobile eClassifieds; Joosk Studio, animation and illustration; Masterpiece Group Myanmar, business process outsourcing; Mote Poh, employee benefits-as-a-service; Natural Farm Fresh, Agri-tech; Ezay, rural eCommerce; and Kyarlay, baby products eCommerce. Covid-19 has changed how people think about investing, at least for now. Funds were quick to offer advice that more or less said: spend less money while making the same money or more money. Which raises the question, what were companies doing beforehand? Of course the first response is that growth costs money and startups should be growing exponentially. But there’s a wider observation here which the market is closer to accepting: supporting growth at any cost and really nasty unit economics, probably isn’t always the smartest investment you can make.

What happens next? This is the question on everyone’s mind. Do we see a L-U-V? For the uninitiated, these letters indicate the possible shapes of economic recession and recovery and - spoiler alert - no one knows which it’ll be. “V” sees the economy bouncing back, “U” a slower recovery and “L” a very long / slow one. The most common sense analysis that your writer has come across suggests that the recovery will be sector-specific; regardless of the overall shape, the shape for different sectors will differ. As investors, that means finding the sectors that are going to look more like “V” than “L”. Right about now readers of this post are probably thinking of delivery businesses as hot new sectors, but we’d caution that such business has seen an increase in demand (not a decrease as many sectors) and this demand may lull as restaurants and shops open again. And so we have to think a bit harder. Unfortunately, we’re not about to reveal all the sectors that will bounce back with a vengeance, because we don’t know. We do believe that more people in Myanmar will continue shopping online as they’ve been forced to experience its convenience, and we expect that this increase of demand will help buoy eCommerce in general. Other services going online may also fare better than before Covid-19, though not all. Will people buy more cars to avoid public transport? Probably those who can afford to will, but private vs public transport is a very income-driven choice in emerging markets. People are not suddenly better off. In fact, the economic impacts are going to hit the broad majority of people, just think about key affected sectors: tourism, apparel, agriculture, fisheries, F&B. That’s not part of the economy, that’s the economy. Meanwhile, investors have dry powder (i.e. money to invest) and will be supporting their existing portfolios, but also continuing to make new investments. With that acknowledged, let’s say for the sake of argument that whatever happens next there’ll be some new investments being made. Here enters the role of the Schumpeterian entrepreneur: the trail blazer who spots opportunities, takes risks and creates value which disrupts the market. Heed this: consumers and businesses are going to be looking for innovations that help them through the more challenging times ahead. Innovations are not inventions. Invention is making a light bulb, innovation is everyone using light bulbs in their homes; innovation is the commercialisation of invention. Some countries are great at invention and innovation, others less so. But, innovation can be imported from abroad (just look at China’s growth since the 90s). We’ve seen successful and unsuccessful attempts at startups using business models already popular abroad to launch products and services in Myanmar. Obviously, not all ideas that work elsewhere will work here. But many will. We’re not suggesting for a moment that starting a business from scratch and making it a success is easy just because the idea works somewhere else. We know that it isn’t. What we are saying is that there are tough times ahead and entrepreneurship is going to be a key component in prospering through them. And so, to anyone reading this who has recently started a new venture, we commend you. Entrepreneurs break boundaries because they take risks, and that takes guts. Got an idea? Innovation requires executing on ideas; “Vision without execution is hallucination”, meaning that it's putting the idea into action that’s the hardest part. We can all dream of flying cars, after all. To help guide your idea, we’ve developed a pitch deck template for you which asks you to answer certain questions. Feel free to use this next time you’re pitching. And, if you’d like our feedback, send it over and we’ll let you know what we think! [email protected]. EME was the first investor into rural eCommerce platform, Ezay, just three months ago. Today, Ezay has raised its second round of USD 200K in order to continue the rapid expansion of its retailer and wholesaler network.

Ezay connects rural mom’n’pop retailers to wholesalers via its platform and provides same day delivery. This is a sea change for these shopkeepers, of which more than 90% are women. Previously they would have to leave the shop to travel to town or convince their spouse to do the same, but with Ezay they receive deliveries to their store and get a wider selection and better prices of products. Starting just three months ago from zero, Ezay has over 1,600 retailers to-date. Leading this round is Seiji Kurokoshi, the impact investor who pioneered upside social impact bonds for single mothers, and who has a background in direct to consumer (D2C) models. The overwhelming majority of Ezay’s customers are women entrepreneurs and Ezay’s model includes many D2C elements. As such, EME and Ezay are both thrilled to have Seiji’s expertise in both the social and commercial aspects of serving Myanmar’s shopkeepers. This is particularly relevant as Ezay is currently working in partnership with leading Myanmar MFIs to offer finance to these shopkeepers - 75% of which have had no access to finance in the past. In Myanmar, only around 25% of people have any sort of formal financial services. Ezay is helping provide access to the most rural users and in turn plans to reach out further into communities via these shops in the future. Ezay’s founder and CEO, Kyaw Min Swe, said “I’m pleased to be able to bring people into Ezay that understand and want to support our journey. We’re growing very quickly and having further expertise to aid our growth will help us reach our goals of serving 8,000 retailers by the end of 2020. The current concerns about hygiene and health are also leading to an increase in the need for our services, so we want to ensure we’re there for our customers during these times”. Seiji said, “I wanted to invest in Ezay as soon as I met the founder, Kyaw Min Swe. His drive to help Myanmar rural communities and his ability to make it happen both struck me immediately. When I looked at the amazing traction that Ezay has had in just three months, my mind was made up. I’m very pleased to be able to support this great company and its mission to improve the lives of rural Myanmar women”. EME is joining the round and continues to work closely with Ezay as the company expands in geography and services. Ezay was the seventh company to enter EME’s portfolio of eight companies. It is the second company in the portfolio to receive outside investment, following Joosk Studio which raised funds from Nest Tech VN earlier this year. La Woon Yan, EME’s Senior Investment Analyst said, “we couldn’t be happier with the amazing progress that Ezay has made since our investment just a few short months ago. During these turbulent times, it’s especially important for us to support great founders and great missions and Ezay is directly helping with keeping shops stocked and reducing the need for women to travel.”. ... Seiji Kurokoshi’s company, Digi Search and Advertising, helps companies to adopt direct to consumer (D2C) models in Japan. He also has COEBI Incubation Office, a AAA incubation centre where he supports and invests in social entrepreneurs. Upside SIBs, mentioned above, are a public private partnership where repayment is made through increased tax revenues. Above: Nang Mo (4th from left) and Soe Lin Myat (3rd from right) with members of the EME Myanmar team

EME has made its largest investment to-date, investing alongside United Managers Japan Inc. for a combined USD 750,000 into Kyarlay, Myanmar’s leading baby products ecommerce and delivery provider. Kyarlay was co-founded by husband and wife Soe Lin Myat and Nang Mo while expecting their first child. Frustrated with poor choice and availability of well-priced and high-quality baby products, they saw an opportunity in helping make parenting in Yangon safer and more convenient. Both Soe Lin Myat and Nang Mo previously worked for the tech giant Garena and have been able to apply leading technology to Kyarlay, while maintaining an approach tailored to the Myanmar market. Their stores are open seven days a week and double as fulfilment centres, making Kyarlay the only company able to provide safe and efficient delivery within just a few hours. Kyarlay has also created a strong community among young Myanmar parents, including with their app and website which include videos and content from Myanmar’s leading paediatricians and obstetricians. By creating a community around their business, Kyarlay is able to continuously learn more about their customers. It’s due to this community that Kyarlay recently started to develop their own branded products for the Myanmar market – meaning they’re able to offer quality items for a lower price to their customers. EME Director, Hitoshi Ikeya said, “We’ve been watching Kyarlay for a while and we’re so pleased we’re able to support them, especially during this volatile time when others might shy away from new investments. Soe Lin Myat and Nang Mo have proven their ability to develop a leading business and EME is thrilled to join them in their journey. We’ll be helping to bring new and exciting products to market, but right now we’ll be helping to ensure that Kyarlay has everything it needs to help parents stay home and stay healthy.” Kyarlay marks EME’s eighth investment in Myanmar since launching in October 2018. EME is a VC based in Myanmar and providing significant post-investment support to its portfolio companies to help them scale. EME is backed by private investors as well as the Dutch Good Growth Fund and seeks to contribute to Myanmar’s sustainable economic development by supporting great entrepreneurs who can change markets and deliver true value to consumers and businesses alike. **Q&A with Nang Mo, Co-founder of Kyarlay** Why did you start this business? As a parent you always need certain items, diapers for instance, and you often forget them. In Yangon, forgetting something as simple as milk powder can easily mean a one hour round trip back to the store. We experienced this frustration and saw that we had the skills to address it. We realised that there was a large market of parents just like us and that this market was growing. We each applied our core skills and started Kyarlay, adding the app and 4-hours delivery late last year. What makes Kyarlay different from regular bricks and mortar baby stores? Our community-driven approach really helps us to be closer to our customers. We’re able to share with them and in return learn more about their challenges. It’s this community approach that drives our business, whether it's later opening hours so parents can visit one of our shops after work, or competitions and promotion within our app that helps parents engage with one another. We launched our 4-hour delivery because we realised that parents need items on the same day and our community and customer focus helped us to understand that. Why did you choose EME as investors? When Kyarlay started, there wasn’t an institutional investor in the Myanmar market that would invest in this type of business. With EME, they’re here in our market and understand our model and approach. While many VCs might think having bricks and mortar stores is a barrier to scale, EME have supported this approach from the start and understand its importance in this market. We’re looking forward to having people close by that we can brainstorm with and depend on. What’s your vision for Kyarlay and how will EME help you to reach it? We’ve recently launched our second store and we plan to open lots more in order to serve the whole of Yangon with our 4-hour delivery. As we build our store and delivery network, we’re really looking forward to being able to provide additional products – such as the private brand products we’re producing now. Once we can serve the whole of Yangon with competitively priced high-quality products then we’ll start branching out further. Our plans will require constant adjustment and a lot of operational savvy, so we’re very happy that EME can be nearby to help us with this physical and digital growth. We’re just about keeping our feet on the ground after an incredibly exciting 2019. We added five great companies to our portfolio last year and established a team to help that portfolio grow. You could say we went from zero to one. But enough about how great EME is; what this post is about is how we build on what we’ve achieved to make sure that in Jan 2021 we’re asking ourselves the same question as this year “how do we top last year?”. We’ve given it some thought and decided we’d share this with our readers - as many of you may be a part of our 2020.

Engage Strategic Stakeholders EME provides a lot of hands on support to our portfolio companies and this starts as soon as we invest and continues for as long as we’re adding value. With a portfolio of seven (soon to be eight…) companies, we have plenty of exciting work to do. But we recognise the benefits that a strategic player can bring to a startup. There’s untold value in someone who’s learnt the hard way, understands the problems that exist in particular sectors or business models, and has networks and expertise in a specific field. That’s why this year we’ll be bringing together new strategic stakeholders with our portfolio companies to help them receive the best insights and expertise to help them expand in Myanmar and across the region. Seek Synergy in New Investments EME is sector agnostic. The Myanmar startup ecosystem is still developing and so we invest in the best startups and founders that have the greatest potential. With a healthy portfolio which includes B2B and B2C startups, we’re better equipped in 2020 to find synergy between our portfolio companies and new investments we make. Right now our portfolio companies have customers inside the home and at the office, in urban and rural areas, and purchasing on and offline. We see strength in diversity and this year we’ll be especially looking for companies that can leverage and contribute to the skills and experience in our portfolio. Work With Partners to Expand Our Knowledge We’ve learnt a lot in the last couple of years and yet there’s always so much more to learn. Henry Ford said that anyone who stops learning is old and anyone who keeps learning is young. Whether you prefer Bob Dylan’s classic or Alphaville’s 80s rendition, at EME we’re planning to stay forever young. We’ll be engaging with new partners, where together we can expand our joint understanding of investing in the sustainable development of Myanmar. If we’ve learnt one thing, it’s that startups in Myanmar can experience phenomenal growth in short periods when they solve a real problem with a truly valuable solution. By enhancing and expanding our knowledge, we aim to increase our advantage for uncovering big problems and the founders solving them. Get Close and Personal To-date we’ve used our newsletter as our main mode of outreach (aside from lots and lots of one on one meetings). This year we’ll continue with our newsletter, but we’ll also be working on some new means of getting closer to our market. We won’t be throwing regular cocktail parties (although we will pull all the stops out in Q4 for our birthday). But we will seek to set up some small, intimate get-togethers where we can cosy up with founders, would-be founders or even corporates looking to work with startups and their founders. We’re working out the details, but we think it’s time to get a little closer now that we’ve built some solid traction and have a lot of lessons and insights to share. Hire Someone Special (Tell Your Friends) We’re a small team that works hard and we enjoy what we do. We don’t expect to have regular openings in our core team, but a position that we tried out last year turned out to be extremely valuable. Sadly, our young protege was always set to leave us for further education, but this means we’re hiring. We don’t consider EME to be ‘just another company’ and therefore we’re not looking for ‘just another employee’. We’re seeking a young, Myanmar individual who wants to build their career working with startups. It’s a very junior position, but it has every potential to grow into something much larger - as EME itself is growing rapidly. We’re looking for someone to mentor and invest in, or as Richard Branson puts it: someone we’ll train so well that they can leave, but treat so well they won’t want to. It might seem a stretch to put a single junior position in a blog about our year ahread, but that’s how seriously we take this role. If you’re reading this and have a tingling sensation about working with us, you’d do well to drop us a line. Full JD on our careers page. … If you read any of the above and thought along the lines of “hey, I’d be interested in…” then drop us a line. We tend not to bite and we’re always very happy to get coffee or beers and chat through some ideas, whether that’s a new venture, partnership or just putting the world to rights. Reach us at [email protected]. From left: Thet Paing Kha - Joosk CEO, Soe Moe Kyaw Oo - Nest Tech Managing Partner, Hitoshi Ikeya - EME Investment Director, and Zeyah Htet - Joosk CSO Nest Tech VN has led a six figure equity investment into Myanmar’s leading animation company, Joosk Studio. EME, who invested into Joosk last year joined the round. Joosk Studio is a creative digital animation agency founded and run by artists Thet Paing Kha and Zeyar Htet. Joosk has worked with companies including Facebook, CB Bank and Telenor as well as NGOs, UN agencies and the World Bank Group. In September 2019, Joosk’s proprietary animation series, Sassy Bound ("BeBee and friends"), won the company the Myanmar Influencer of the Year Award for Art and Design. Joosk is doubling down on its popular comic series and producing BeBee The Animated Movie, while continuing to grow its core agency business. Joosk’s debut into cinema will bring Myanmar’s first feature length animation to viewers across the country. Nest Tech VN’s Managing Partner, Soe Moe said, “Joosk have created a great business, serving high profile brands with their unique and funny animation. We’re excited to be a part of this movie, as well as helping Joosk to continue to build their creative agency”. EME Myanmar joined this round, marking our second investment into Joosk Studio. EME’s Investment Director, Hitoshi Ikeya, said, “we’ve loved working with Joosk and we’re pleased to be able to continue to help them innovate and bring creative content to Myanmar companies and consumers alike.” Q&A with Thet Paing Kha, CEO of Joosk Studio What does this latest round of investment mean to Joosk Studio? At Joosk, we use humour and illustration to reach audiences and share messages. We’ve been running our Facebook comic series alongside our agency work for a while now and this latest investment lets us develop that side of the company to bring our audience something bigger than they’ve ever seen before. While everyone is very excited and already working very hard on the movie, we’re also continuing to find exciting new ways to serve our business customers. We’re fortunate enough to work on interesting projects - both for NGOs and private companies and we see a lot of synergy between the movie and our core business. Creativity seems to be such an important part of what Joosk does, how does taking on new investment affect that? We’re very lucky that our current investors, EME, have always given us 100% freedom when it comes to any remotely creative decisions. When we met with Ko Soe Moe from Nest Tech VN we got the same feeling and had many casual meetings to make sure that we were a fit for each other. We also see that Nest Tech have a lot of digital skills that could help Joosk with digital merchandising and discovering new ways to entertain our audience outside of traditional approaches. When’s the film coming out and what’s it going to be about? BeBee The Animated Movie will be in theatres nationwide sometime in 2021. For now that’s all the information we’re sharing I’m afraid, but we’ll be releasing some clues and hints in the coming months! One thing is for certain, if you’ve ever enjoyed anything we’ve made before, we’ve got a very good feeling you’re going to love what we’ve got coming! Above: Ezay Founder and CEO (centre) with EME Investment Analysts Hla Win New (left) and La Woon Yan. EME-Myanmar has led a six-digit seed round in Ezay, a Yangon-based rural ecommerce startup for rural Myanmar retails outlets, together with one of the most influential startup founders in Myanmar. Founded in August 2019 by ex-Oway employee, Kyaw Min Swe, Ezay is helping to revolutionise commerce for rural retailers. Ezay provides a mobile platform that connects rural ‘mom and pop’ shops with wholesalers and provides delivery for all goods. Previously retailers would have to visit multiple wholesalers several times throughout the month, with no remuneration for that lost time. From today, retailers can re-stock at the click of a button. EME’s Investment Director, Hitoshi Ikeya said, “We often hear people talking about ‘digital leapfrog’ in Myanmar but this investment really represents the value that mobile solutions can bring to rural communities across the country. Kyaw Min Swe is a great founder and we’re very excited to support him with his mission”. Kyaw Min Swe at a recent Ezay retailer townhall event

Q&A with Kyaw Min Swe, Founder and CEO of Ezay How did you come up with the idea for Ezay? My sister has a small shop in rural Myanmar and each week her and her husband need to drive to the various warehouses to restock. This is a real burden and it’s common across Myanmar; often the husband will go to the wholesaler but must take time off work to do so. Choice is also limited by the common fact that most people will buy from only one or two wholesalers. I saw an opportunity to address this issue and connect wholesalers and retailers through a mobile platform - providing delivery to make life easier for retailers. What impact does Ezay create for companies and users? Retailers love Ezay because for the first-time ever they’re able to buy online for the regular shop stock needs and get the products on delivery the next day - all for the same price they’re currently paying to shop offline and fetch their own goods. Wholesalers are thrilled to have more frequent orders and have regular collections from a wider-rage of customers. They’re able to think about their promotions through the app and really become more efficient throughout their business. Why did you select EME as investors? EME’s directors and staff have been really supportive of my vision and have helped Ezay even before their investment. For an early-stage business like Ezay I think it’s vital to have people behind you that understand your vision and can contribute to making it a success. With EME I felt they were very interested to support Ezay, but also that they trusted me to execute my ideas. What is your vision for Ezay in the next 5 years? How will Ezay help change rural retail landscape in Myanmar? Ezay is just getting started. Right now we’re onboarding new retailers all the time and we’re upgrading our platform to make logistics, payments, and commerce faster and easier. We plan to expand rapidly across Myanmar once we’ve proven this model across our key villages. Our expansion will be both in area and also in services: as we develop a closer understanding of the retail supply chain and customer’s preferences we can adapt to serve those needs in new and exciting ways. We’ve got a few ideas of how this could develop. For now we’ll just say that we intend to continue to offer real value to people that others have struggled to serve and create new opportunities for them while doing so. About Kyaw Min Swe Kyaw Min Swe is a committed and experienced professional with a proven track record. He was born and raised Nattalin, a township in Tharrawaddy District of Bago. He worked in Dubai and Singapore for five years and came back to work as the COO at Hello Cabs, and later at Oway as the Business Head. He stared Ezay based on his first-hand experience of the problems facing rural retailers and because of a passion to help rural communities embrace the benefits that technology offers. Above, from left EME's Team: La Woon Yan, Hitoshi Ikea, Hla Win Nwe, Matt Viner, May Phoo Maung Maung, Claire Lim. On Wednesday, 20th November EME celebrated it’s 1st anniversary and announced two new investments it has made into Myanmar-based and Myanmar-led startups: Natural Farm Fresh and Yangon Broom. EME invested a six figure amount into Natural Farm Fresh, along with co-investor United Managers Japan Inc. (UMJ). Natural Farm Fresh produces high quality chilli and other dried food products at competitive prices, using locally produced solar dryers to increase yield value and produce products without dangerous aflatoxins. EME’s investment will help Natural Farm Fresh to scale up, develop new products for other markets and start to introduce digital technologies throughout the supply chain. Founder and CEO of Natural Farm Fresh, Nay Oo said, “This investment is very rewarding, not just because it will help us to grow but because EME really shared our vision to help bring quality products to the Myanmar market, improving health while providing more income to farmers across the country”. EME Director, Hitoshi Ikeya said, “We’re thrilled to make this investment. We’ve been building a great relationship with Ko Nay Oo over the past months, love his vision and have already seen his ability to execute. The chilli market in Myanmar is well over $100m and growing; regionally, the numbers are even higher and together we’re very well placed to take advantage of this huge market potential.” Above: Nay Oo, Co-Founder and CEO of Natural Farm Fresh EME, along with co-investor NestTech VN (a Vietnam-based VC), invested a five figure sum into Yangon Broom, a Myanmar home-services startup. Yangon Broom provides on-demand services to home and businesses across Myanmar’s bustling Yangon. Currently, services include cleaning and ironing, but the company has more verticals to roll out in 2020. Founders Kyi Min Han and Kyaw Min Tun come from backgrounds in recruitment and building maintenance, a winning formula for high-growth businesses that contract hundreds of staff. Co-founder and CEO, Kyi Min Han, said, “The whole team is very excited to have two great investors behind us to help take Yangon Broom to the next level. We’ve built our business around people as we aim to provide safer jobs for women in Myanmar, and these two investors will help us protect that while we grow.”. EME’s investment philosophy includes providing significant hands-on support post-investment, operating a full-time team who work closely with companies to help them scale. Matt Viner, EME Investment Manager said, “We’re so fortunate in Myanmar to have such passionate founders. Kyi Min Han and Kyaw Min Tun pay close attention to their most valuable assets - their staff - and in turn, they’re building a strong business. We’re looking forward to helping Yangon Broom quickly reach 10X growth in total bookings, bring in new tech with help from NestTech VN and add more services.” Nest Tech founder, Soe Moe Oo added, “Nest Tech is delighted to be investing into Broom. The two Founders truly care about making a difference in people’s lives, especially those amongst the more vulnerable in society. Not only are jobs being created, but a caring community culture is being developed too”. Above: Yangon Broom's Team including CEO Kyi Min Han and COO Kyaw Min Tun

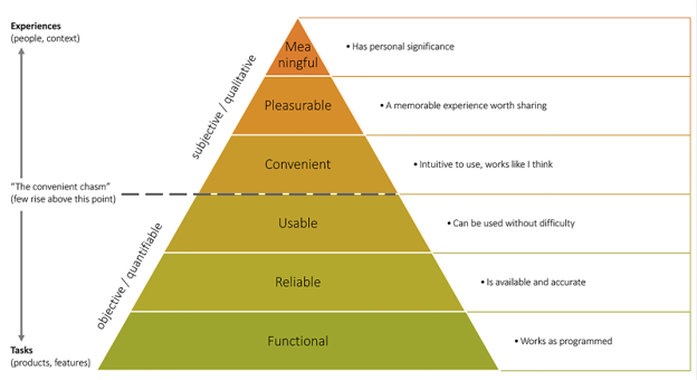

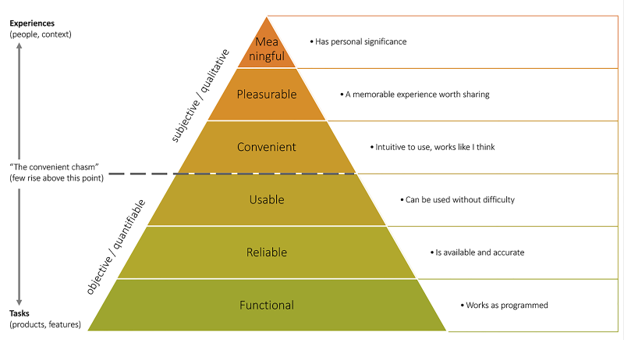

Earlier this month, EME joined nearly 2,000 leading experts from the marketing industry at Mumbrella 360 Asia - the region’s largest marketing and media conference, held at Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands. At this conference, the industry’s biggest players come together to forge connections, ask pressing questions and share their secrets and strategies to achieving success. Speakers and panellists were invited from leading global companies such as Unilever, Johnson & Johnson and Prudential; tech giants like IBM and Netflix; media leaders such as CNBC; NBC Universal, BBC and Vice; and up-and-coming companies like Lazada, TikTok and Twitch - all of this in addition to the marketing industry’s biggest firms: Ogilvy, Kantar, Hubspot, UM and Accenture to name a few. As you can imagine, it was an action-packed two days of knowledge sharing and information overload. In this blog, we share some of the things we learnt. Promotion by Emotion Several of the keynote speakers emphasised the need for brands to strive to push out emotional content, rather than the typical barrage of rational and functional marketing messages that brands constantly churn out. Why? Because emotional content is more likely to be shared and engaged with, and it is also more likely to be remembered by the consumer brain. Since consumer behaviour is 99.9% driven by the highly emotional subconscious, there’s an emergence in neuro-marketing among companies and agencies, as well as media companies, for getting their messages across. This means marketing with behavioural economics instead of neoclassical economics - instead of using typical functional selling points like “a product is cheaper, bigger and tastes better”, there is now a shift to “a product gives you happiness, makes you feel safe and strengthens your relationships”. Coke’s “Choose Happiness” is a strikingly obvious use of emotional marketing. Trigger Happiness We learnt that while generally an average of 50% of purchases come from word of mouth, 80% of what triggers word of mouth is good brand experiences, not only functional from end to end (everything works, nothing is broken) but also meaningful (not only is nothing broken, it was so easy to use because my needs were anticipated). To take this up another gear: company’s should aim for pleasurable experiences (not only is nothing broken and the platform quite easy to use, the content was hilarious and brightened my day). Where can customers rank their experiences with your brand?

(For)give Me Another Try Building close relationships with customers is also a good hedge against future misdemeanours. Customers who have a connection with brands and companies, whether with positive brand associations or great brand experiences are not only more likely to make a purchase or tell a friend (this we knew already), but they are five times more likely to forgive a brand for mistakes made. This is crucial in the world we live in, considering such mundane things like a five-minute response delay or misspelled customer name could result in customer loss in this age of fast-paced and hyper charged customer service (the age of the pampered customer). Just (keep) do(ing) it Big brands are becoming all about predictive personalisation. That is, using data-driven content automation to enhance customer experiences and keep people coming back. In our digital age this is as easy as simply relying on users’ behavioural history with the brand’s platforms in order to determine the perfect algorithm for developing content that their users will find interesting, engage with and most importantly lead to sales or conversions. If you’re still unclear what this means - just scroll through Facebook and note that you keep seeing more cat videos ever since you spent a whole day watching cat videos. Go your own way Lastly, we learnt that we should be wary of “best practices” because it’s those disruptors who break the mold of best practices that truly find success. Startups and early stage companies especially are most likely to pattern growth strategies based on existing companies, which could be a crucial mistake[c1] . From a VC firm’s keynote we learnt the key steps for bootstrapped growth: identifying the brand’s purpose, building brand assets, identifying platforms, developing powerful stories, growing advocacy and loyal customers and of course, tracking. This is a good guiding light to follow, since doing too much in the short-term could be harmful for long-term growth if these short-term activities are not linked to long-term strategies. All in all, it was great to link up with the region’s very best marketing professionals, and we can’t wait to take back everything we’ve learnt and apply them towards the growth of EME’s fast-growing portfolio companies. Do you agree with what we’ve shared? Have anything to add? Drop us a line at [email protected]. Myanmar – land of the digital leapfrog! More phones than people! It’s all true, but stating that something is, is not the same as stating what it means. Does it mean that digital infrastructure is changing millions of lives every day? Yes, we’d say so. Does it mean rapid adoption of mobile applications by a great proportion of Myanmar’s 50-60M population? No, not really. Is there a range of startups successfully taking advantage of digital leapfrog Myanmar? There’s less of a “range” and more of a “few”. This post tries to lift the fog on Myanmar’s leapfrog headline and uncover some truths to success in this now famously digitising economy.

Let’s start with some basics from a macroeconomic perspective. Myanmar has the lowest income per capita of any SEA country. When incomes rise, people have a greater ability to consume. To begin with, most of this consumption is taken up with better food – meat and sugar consumption increases. But until incomes rise beyond around USD 3.5K (Indonesia today), people don’t tend to spend much more on non-essentials. At around USD 5K (China in 2010/11), things have changed significantly: people buy pets, vehicles and other luxuries. Myanmar is at USD 1.5K on average. That means the average person is giving one thing up to get another. Evidencing this point, one study of rural solar home systems (in Sub Saharan Africa) found people who bought the systems would then consume less meat and sugar. This leads us to two observations: 1) let us think more about 10-20M then 50-60M people if we’re selling even a low-price product, because a lot of people just can’t afford new things. 2) If people are going to sacrifice nutrition to buy your product, it’s going to have to more value than a balanced diet. That’s some real value we’re talking about – in the example above, people with a solar lantern have clean light inside the home and avoid smoke and fuel costs and danger of fire. Even Candy Crush can’t compete with that. Unless selling to the very low income, people may not need to give up sustenance for your product but the concept remains: all decisions include giving up the next best option (opportunity cost) so you have to deliver tremendous value to have people choose your product / service. Indeed, the Irrawaddy recently stated that minimum wage earners spend 85% of their income on rent. The next issue is best expressed in plain terms: if someone with limited education or need for an electronic device suddenly has one, they’re going to receive less immediate benefit from it than your average urban college kid because they simply won’t appreciate how to maximise its utility. People often talk about “customer education” – upskilling the customer to use your product. The conversation goes like this: “OK, it’s a good idea, but will people use it?”, “Yes, we just need to make sure we do a lot of customer education.”. That’s fine in principle, but education in general has huge free rider issues, as any garment factory owner can attest to. Example: If factory A provides training at a cost of $10 per person per month, factory B could hire the person for $5 per month more salary after they have been trained Factory A. In other words, customer education is expensive and there’s little guarantee you’ll see a return on your investment (you could teach customers to use your ride hailing app, but then they’re better equipped to use all ride hailing apps). How then, do you create a product for the mass market that people will use? Let’s consider Bagan innovation Technology (BiT) (not an EME portfolio company). BiT have around 14M users of their Burmese language keyboard. They got into the market early with a solution that everyone needed. They also have a bookstore. To drive people to the bookstore, they leveraged monks and monasteries – places and people of education. Finally, they have a fortune-telling app that is growing exponentially – BiT tapped into something people are already spending money on and made it cheaper and more efficient. In summary, to reach millions you have to offer something useful, better than the alternative and that people find true value in. The key is “people”: unless you fully understand your customer, you can’t know what they will value. A final point on reaching scale in Myanmar. In fact, in Southeast Asia because this isn’t unique to Myanmar. There is a lot of reason to consider offline and online approaches to reach or maintain customers. Tech has leapfrogged, but trust is catching up and offline approaches are easier to trust in (see a person, touch a product, go somewhere to get service, etc.) Just look at Shop.com.mm with their agent model or bricks and mortar shop, or BiT who initially reached customers through monks. The same is happening in Indonesia with Bukalapak agents or Storeking in India. People often don’t want to consider the expense of being offline and there’s little hype around opening shops (versus launching apps) but in markets where trust is limited and exposure to technology is still new, there’s a good reason to go beyond Facebook marketing to scale. That reason is: unless you innovate in how you reach and maintain customers not just your product, you’re unlikely to succeed in this economy. Twelve months, six investments, three new hires. Since launching in October 2018, EME has had a stellar year, if we do say so ourselves. We’re not getting ahead of ourselves yet though. As we see it, we’ve set a high bar for ourselves for 2020 and beyond. When we meet startups we often ask what they’ve learnt in their short-lived experience trading as a company. There are no magic answers to this question, rather it’s a way to see how founders reflect, adapt and strategise. This post focuses on our reflections after twelve months investing in early-stage companies in Myanmar.

1. Relationships Matter Strong relationships are formed over time and through good and bad times. When things are good, relationships tend to be easier. When things are challenging, relationships can either grow or suffer. We see that this comes down to trust. As investors, we ask ourselves “is this a founder / team we can trust to overcome challenges?” and startups should be looking to EME asking, “can I trust this investor to back me when things don’t go to plan?”. Great companies become great often by pivoting many times (Slack started life as a video game). Pivoting means admitting the first plan isn’t the right one and pursuing a new direction and for that there needs to be a lot of trust among both investee and investor. It’s hard to explain when the occasions arise where trust is deepened, all we can say is you’ll likely know when they arise. In these times, we try to be cognisant about the decisions we make today and how they affect the trusting relationship that we’ll need in the years to come. 2. Support is Crucial Early stage companies in any market need mentors and advisers to succeed. In a frontier market such as Myanmar, this is even more true. In our experience, supporting entrepreneurs is about helping them to achieve their vision. This could involve a range of things, from analysis and strategy to direct support in sales and marketing. Most importantly, it’s about working with, not against, the entrepreneurs and their team. When we make an equity investment, we’re literally buying our way to becoming a part of the company and this comes with a lot of responsibility. Our investors have trusted us to find and help scale the companies of tomorrow, and the only way we’ll help great entrepreneurs create amazing companies is by letting them do what they do best. As investors, we don’t want to change or lead the strategy of our portfolio companies, we want to encourage them to push further, take risks and do those things that will redefine markets in Myanmar. To do that, we’re constantly looking inward about our support, its effectiveness and how we improve. 3. Research is Priceless Being inside the market is crucial to investment decision making. This is true anywhere but again more so in markets that lack data, infrastructure and are going through economic transitions – like Myanmar. Our investment analysts live and breathe the market we invest in and they’ll write a full in-depth research report about each startup we present to our investment committee. This report is the output of weeks of intensive research, not just desk-based but being out in the market interviewing, testing, ordering, etc. It’s a lot of work, but it’s integral to our approach and has helped us identify truly unique companies. And it’s not just research into companies, but sectors too – EME is sector agnostic, but by researching individual sectors, we deepen our understanding of the companies within them. We’ve summarised this internally as “working with intellectual integrity”: to listen, question, test and think without bias. 4. First Impressions Last The fabled elevator pitch. Those few minutes you have to impress/sell to someone before the meeting is over and they’re gone, perhaps never to call you back or to become your next customer / investor. Most founders are probably tired of hearing about how to deliver the perfect elevator pitch and we’re certainly not going to try that. What we have seen though, is that first impressions are stickier than gum on your shoe on a hot day. This works both ways: make a great first impression and there can be a lot of flexibility afterwards but, make a bad one and you may not bring it back. Pro-tips for anyone meeting us for the first time: read our blog. People are nothing if not easily flattered and seeing you’ve read our blog will show us you care (and that you do your research). We’re also big fans of the “four Hs” (happy, helpful, humble, hungry) and tend to get on well with people who encompass these elements. 5. Questions and Candidness Count Since EME’s inception, we’ve considered it our responsibility to ask challenging questions and give candid, constructive feedback to startups we meet. Whether it’s a very first meeting or a board meeting after we invest, we’ll share our honest thoughts and recommendations. Mostly, the response to this approach is overwhelmingly positive – hopefully some of you reading this can attest to that. Of course, on occasion it backfires. On this note there are three things we have considered: 1) we’re not always right and don’t intend to give that impression, we just say as we see it; 2) we’ve met 150+ startups, so we’re a pretty good barometer of who’s doing what and what’s working / not working (we invite you to pick our brains anytime!); 3) to make an omelette you’ve got to break a few eggs – we’ll continue with the tough questions, to find those who have inspiring answers. Ultimately, we value sincerity and we’ll always be sincere with our questions and feedback. We’ve learnt it’s not always easy, but still believe it is always the best approach. --- We’ve focused here on lessons in our investment approach, more than internal operations. That probably doesn’t do credit to the amazing EME team, which is therefore the final point to this post: being good at anything means building an amazing, inspiring, committed team. I’m honoured to work with my colleagues here at EME and we love seeing entrepreneurs and founders who put their team first. To meet the full team and our portfolio companies, check your inbox for your invitation to our one-year birthday party this 20th November. If you don’t have an invitation, drop us a line and we’ll see what we can do – [email protected]. Above: John Lim, ARA Asset Management (photo credit: DealStreetAsia) We packed our bags and headed to clean and pristine Singapore to meet with and hear from leading regional investors and founders at the DealstreetAsia™ PE-VC Summit 2019. Arriving at the conference, we quickly noticed that we were in a very select minority of investors from Myanmar – an indication of the country’s early frontier status. People were curious about Myanmar and excited to hear about our work and our incredible portfolio companies. Over copious coffees and one or two beers, we shared, listened and learnt. This short post summarises some of the key insights from the presentations, conversations and gentle persuasions of the event. Underlying each of the following points are three core values we observed from the summit: know your customers and put them first, work hard and smart, and lastly, find an investor you can build a relationship with.

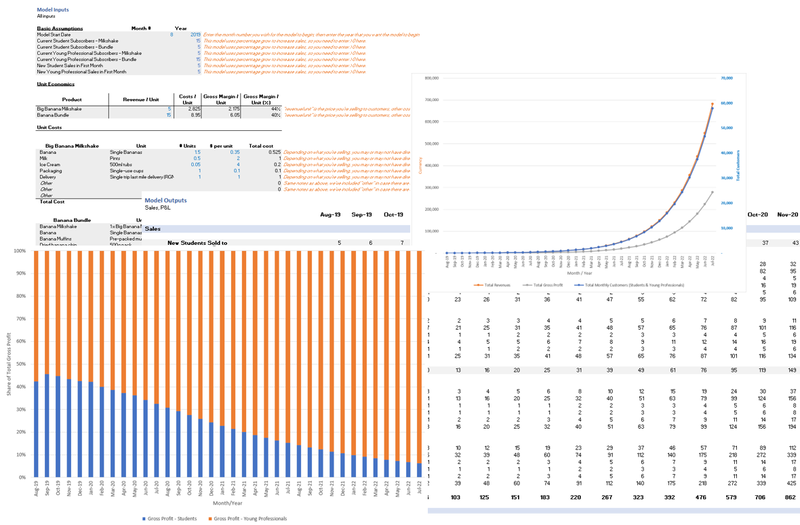

Lesson 1: Don’t Try to Make Money One thing we weren’t necessarily expecting to hear at an event where the total assets under management of all parties was over $100bn was “don’t try to make money”. However, founder and CEO of Deskera, Shashank Dixit told a roomful of investors and founders to focus on building great companies that serve customers and let the money follow. We see value in this sentiment: startups need to deliver outstanding value to their customers - with scaleable unit economics - and if they succeed then exponential growth will happen. Once your product or service is too good to be without, you’re set on a course for scale; so long as you scale with the right unit economics, the riches will come. Focussing on making money, on the other hand, isn’t putting your customer first and introduces short-termism that could prevent you from building something great. Indeed, EME’s permanent capital approach (rather than a fund with an exit deadline), means that we can work with entrepreneurs to build great companies and take a long-term view with founders. Lesson 2: The Importance of Trust One of our favourite one-on-one on-stage discussions was the interview with John Lim. Son of a schoolteacher, John Lim is the cofounder of ARA Asset Management which has $58 billion in assets under management. Lim spoke about how crucial trust was in long-term business relationships, citing that he had a long-term multi-billion-dollar arrangement based purely on a handshake. This introduces an interesting thought experiment: would you trust your partner to honour the agreement purely on a handshake? Often the answer is “no”, which is why we have contracts and may be fine for short-term transactions. When it comes to investing, though, we want to be able to treat contracts as a formality, understanding that there is an enduring trust between us and those we invest in. This approach forces transparency, accountability and integrity on all parties, which can only be a good thing. Keep this in mind next time you review a term sheet. Lesson 3: 007, not James Bond China’s growth has been built in part upon the 996 model: people working diligently from 9am until 9pm, six days a week. This might feel quite gruelling for the employed, but for founders John Lim says they should be following the 007 model. 007, in case you haven’t worked it out yet, is 12am-12am, seven days a week (i.e. 24/7). Of course, even Elon Musk sleeps (a little), but the sentiment is that to build something great, founders must commit and put in the work. In fact, when asked about the secret sauce for founders, Lim offered: there’s no secret sauce for startups or CEOs. They must be passionate, know their stuff, be patient and work hard. He added: “Don’t open a restaurant because you love food. If you want to start a restaurant, work in one, understand the customers, the supply chain and the problems; after a couple of years, only then might you be ready.” Lesson 4: Vision Without Execution is Hallucination Southeast Asia is creating more and more unicorns (startups valued >$1bn), but these companies are coming from great execution more than they are fresh innovation. Given that SEA is quickly developing, there is significant scope to take models born in Silicon Valley or elsewhere and transplant them into these markets. Investors and founders at the event agreed: SEA is an execution game. This is as true in Myanmar as anywhere else and perhaps even more so given the country’s only very recent emergence from military rule. In Myanmar, there are plenty of opportunities to disrupt traditional business with nimble ideas from other markets. How to execute? This requires excellent founders who can deliver on their strategies, who can roll up their sleeves and make things happen, who have a drive and determination to ensure dreams become reality. Decisions might happen in the boardroom, but the real work takes place on the ground. Lesson 5: The days of investing and taking a backseat are over Investing in startups is becoming increasingly competitive. With a challenging global economy and more funds available for a greater array of startups, investors are reflecting on the role they play. Across many conversations and panels, a theme emerged that simply betting on a founder and walking away, hoping they succeed, is a dying strategy. Founders expect their investors to become partners, not just cheque books. In Myanmar, there is less capital than most markets in SEA but this doesn’t mean founders need to be happy just accepting cash. In fact, EME’s model is based on investing capital and significant time into our portfolio companies – helping them to overcome their challenges and find a pathway to scale. Agree, disagree or have additional lessons to share? Drop us a line at [email protected]! A good financial model is a little bit like magic. You can gaze into the future and compare how decisions you make today affect what happens for years to come. Of course, even the best financial model is only a representative of what could happen. None of us can truly see into the future, try as we might. What makes a “good” financial model? A financial model is just a business tool, so a good one is one that gets the job done. It should be error-free, clear to use and provide results that are easy to interpret. Similarly, you need a different tool for different jobs; the financial modelling requirements of a listed company are going to outweigh those of a young startup.

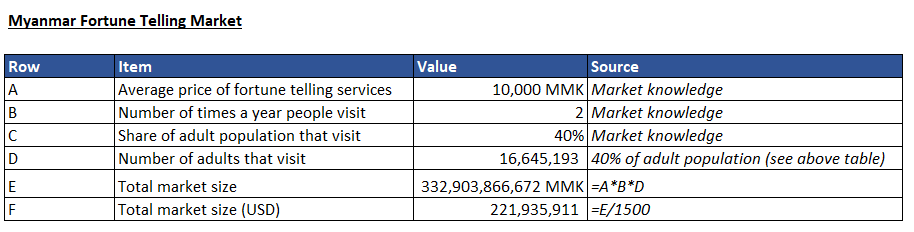

When we planned this post, we were intending to share a financial model template that we’d found online and provide some usage notes / pro tips. However, it turns out that there is a dearth of appropriate models that are ready to use by reasonably inexperienced people. The models we came across were either overcomplicated or very limited, so we decided to create our own! You can download our subscription model template at the bottom of this post, and below you’ll find some good modelling principles to help you make your own. Garbage in, garbage out The first rule when creating projections of any sort is: garbage in, garbage out (GIGO). This simply means that if you make wild or erroneous (or both) assumptions when putting information in, you can only expect to get wild or erroneous results out. If my model says I can take 10% of the total addressable market, but I get the market size wrong, my model will be wrong. This means that the initial research behind your figures is crucial. Research your inputs and check your assumptions as much as possible before entering them into any financial model. You can be sure that investors will ask, “how did you get to this number?”, so be ready to defend your projections. Top down vs bottom up Check out our recent post on top-down vs bottom-up approaches to market sizing. With financial modelling, we also want to start at the bottom and work back. For instance, if you simply estimate your sales are growing at 10% month on month, you can quickly miss the underlying details. Your sales are unlikely to grow for no reason. More likely, you have marketing and sales expenses that together help drive sales. At the very least, you need to consider in detail how your HR, marketing and related costs are going to contribute to increased sales. Rather than assume sales grow at 10% and sales staff expense grows at +1 person a year, ask how many sales one salesperson can make in a month then multiply this out to the year, then work up to sales output. KISS Keep it simple, stupid (KISS) is a design principle that is clear to understand: keep things as simple as possible, so that they’re easier to use. This goes for financial models too: separate your inputs clearly, build your model logically and add notes wherever necessary. Adding usage notes is not only good practice for any spreadsheet design, but it'll help you understand what you've done so far, in case you start to get stuck with your model. If you make a good pitch to an investor, there's every chance they're going to want to see your financial model - so it's good for it to be clean and easy to read. Use charts effectively Don’t rely on people to read hundreds of lines of your model. If your model requires complex calculations that’s fine, but these rows shouldn’t be used to present information. In our template, there are “inputs” and “outputs” plus some charts. This is to keep things straightforward (and our outputs are only 100 lines or so). Another approach is to model sales and revenues separately to costs and then to present the outputs of these sheets in a summary sheet. Whichever you do, it’s advisable to add some charts to show what’s going on in the model. If you haven’t seen it yet, check out our quick guide on what makes a good chart. Build what you need, then stop Think about building your financial model like building a ladder. You need enough information (rungs) for your purpose. You might even add a few extra rungs, to make it easier to get on and off the ladder at the top. But if you keep adding rungs, you’re going to have a very large ladder that’s cumbersome to move around and doesn’t offer much beyond the much smaller one that suits your need. Financial models can go on and on, but there comes a point where adding more variables isn’t necessarily making your model any more accurate. If the model represents key costs, how you acquire customers and how you generate income and adapts to show different outputs based on your input assumptions, it’s probably all you need to begin with. Remember, the more complex something is, the easier it is for errors to hide. It’s better to have a simple and correct model than a complex and wrong one. You can download our basic subscription financial model here. Our intention isn’t to provide a one-size-fits-all model (does such a thing exist?) but rather to guide founders on how to go about representing their business model in spreadsheets. The best financial model in the world won’t grow your business, but clearly laying out how your business makes money should help you make better decisions. Good luck! Above: the EME team (after we escaped) Last Friday the EME team headed out to Xcape Squad, one of Yangon’s escape room venues (they’re not sponsoring this blog). After we escaped, we reflected on some lessons that also apply to founders and startup teams. For those that aren’t familiar with the escape room format: a small group of people is locked inside a room and must solve several clues to unlock the door all within an hour. The time pressure and limited information forces a need for communication and collaboration, something that startups will appreciate as they face pressure to grow / raise before the money runs out.

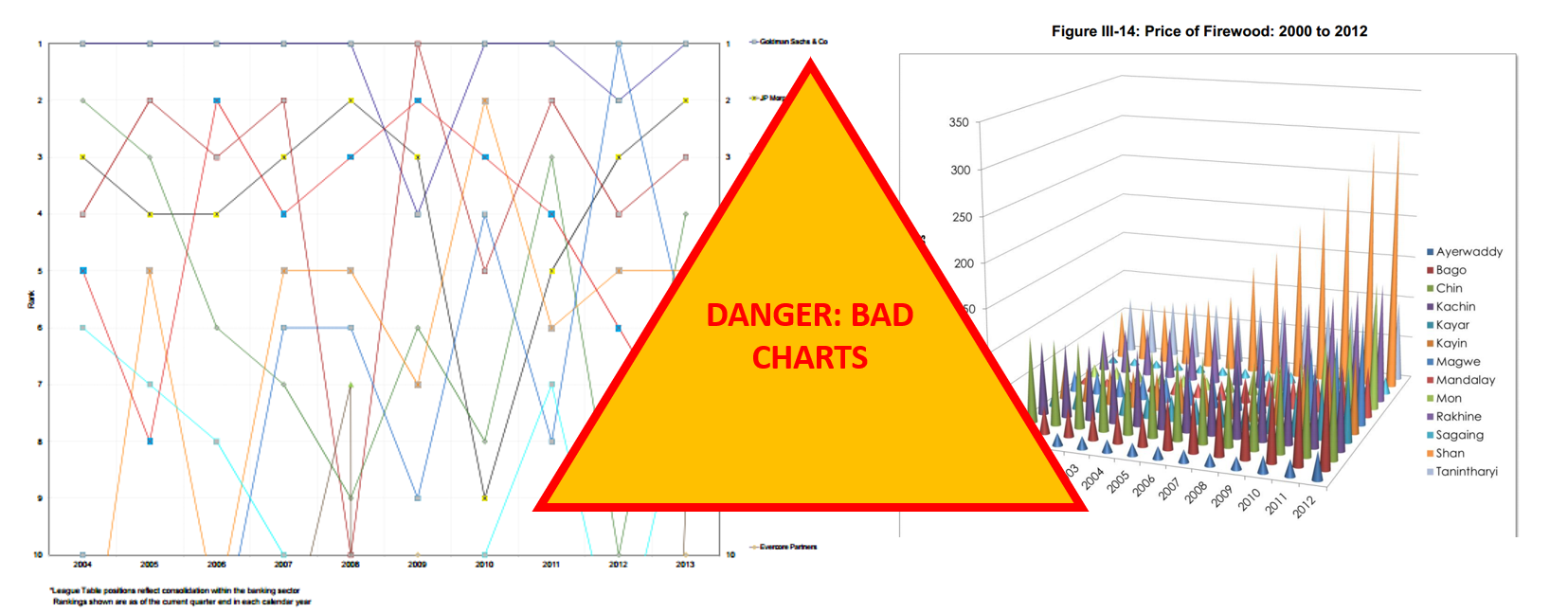

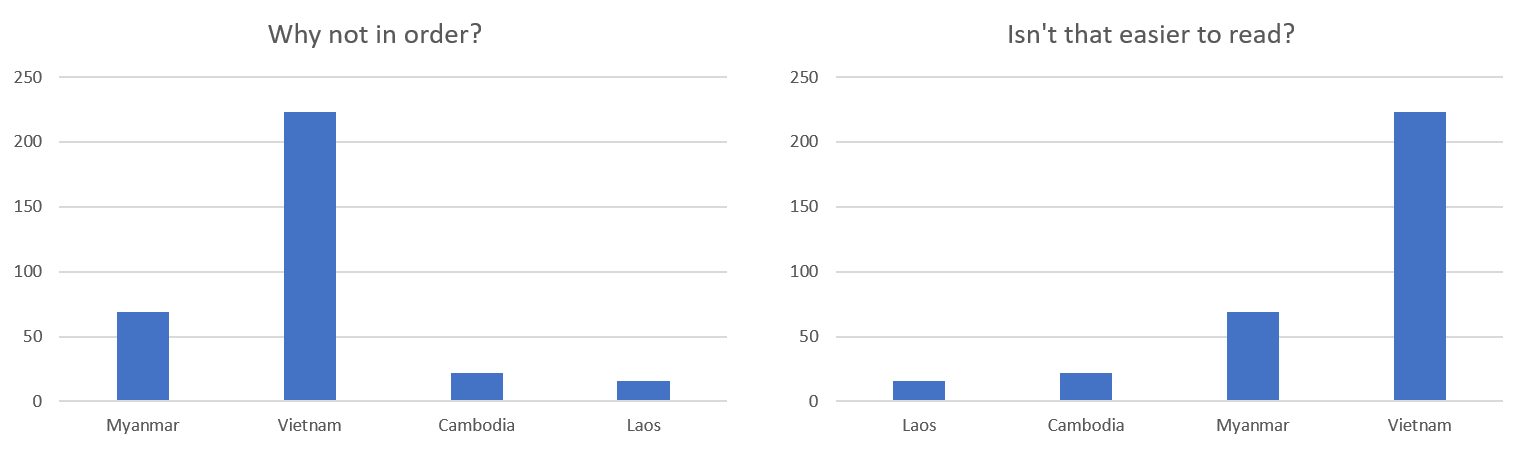

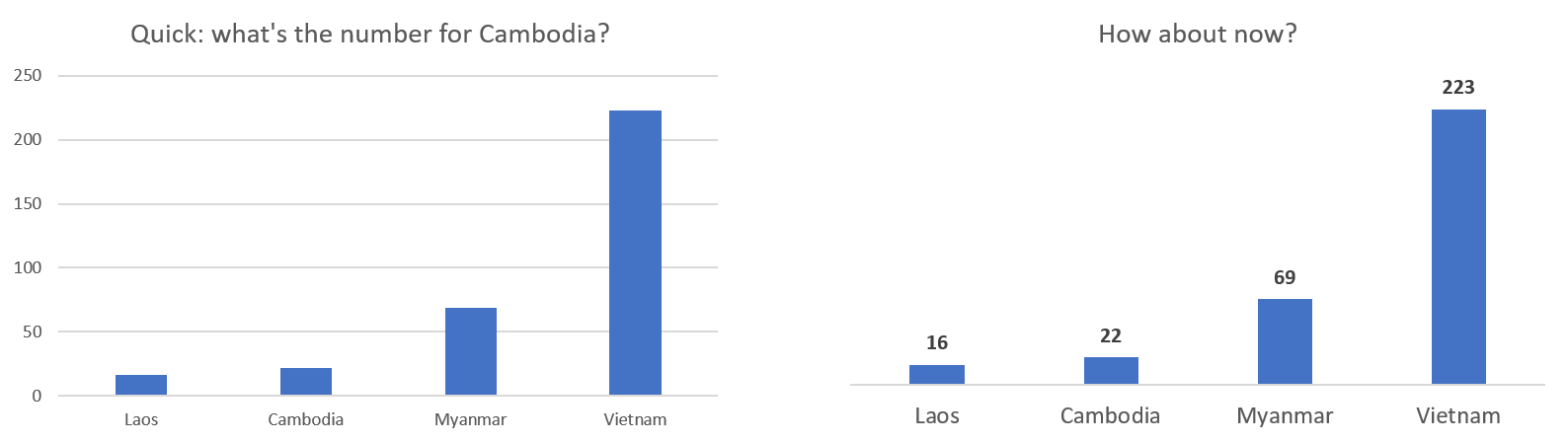

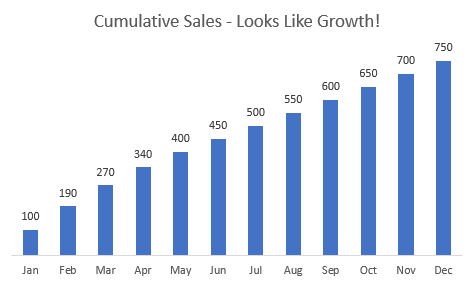

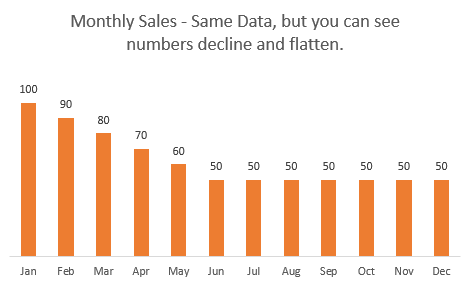

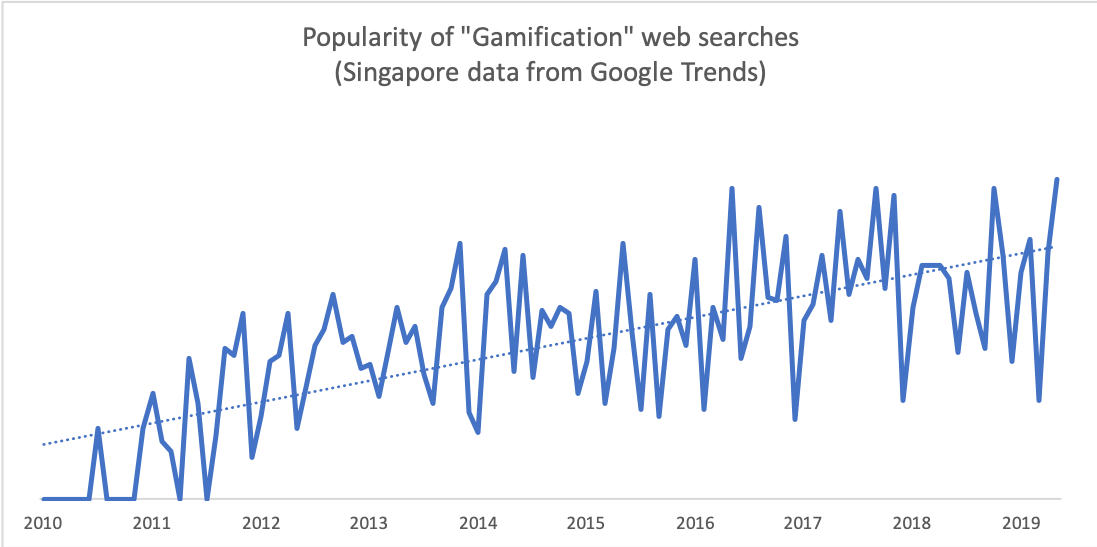

Here’s what we learnt: #1: Map Your Surroundings Before starting off in the wrong direction, it’s important to understand your surroundings – your market, competition, customers. You might have what feels like a great idea, but until you’ve spent time checking your assumptions, your great idea is unqualified. When we got into the room, we found several long sticks and immediately started seeing where they would fit – but there was a very big clue that we missed for a while because we hadn’t properly assessed our surroundings. Startups sometimes make this same mistake by missing crucial elements that affect the viability of their model. To avoid this, ensure you’re consciously aware of who your company is serving, why it’s serving them and why they would use your service over any other. #2 Don’t Forget Fundamentals Escape rooms force you to solve clues in order, but before we learnt this, we were flailing around trying to solve several clues at once. Startups should be fast and nimble, able to race ahead. But, even the fastest startup needs some key fundamentals in place and missing these is going to cause severe growing pains later down the line. Yes, we’re talking about clear financial reporting, sales tracking, customer management, staff management, etc. It’s important that there are at least basic and functional systems in place as a foundation to grow upon. Whether its simple spreadsheets or free / freemium software, it’s also important to keep track of what you’re doing. How else are you going to show your achievements? How can you ensure you’re making the right pivot without a clear record of what’s happened so far? #3 Have a Plan and Embrace Horizontal Structures When there’s just three of you, it’s a good idea to ensure that anyone with a smart idea can bring it to the fore. This is as true for the escape room as it is for business, and it’s not just limited to three people. In a startup you’ll have a small number of people (at least to begin with) with different skillsets and in different positions. Firstly, everyone should understand what the company is working towards and how to get there. Second, this plan should be changeable if new information is presented – by staff at any level. Sales people know why customers are or aren’t buying, the customer service team knows what customers like or dislike about your products / services, the marketing team knows how to advertise key messages, and so on. While the CEO should be plugged into these things, it’s also the CEO’s role to ensure that all staff have a voice and can contribute to achieving or altering company goals. #4 Get Advice To quote one famous sports coach, “In life, you need many more things than talent. Things like good advice and common sense”. We had three opportunities to get help with clues and we used every one. Getting hints to solve clues helped us move faster when we hit a roadblock. This is the role that mentors, advisors and board members (we’ll call them all mentors for now) should play for startups. It’s the founder(s)’ role to find good mentors and “good” is going to be different depending on the startup need or company stage: it could be someone from the industry that brings connections and technical knowhow, or a venture capitalist with ability to help raise additional funding, or simply someone with experience to help bounce ideas off of. #5 Celebrate Wins, But Keep Going When we solved a clue, we high-fived and patted ourselves on the back but as we were against the clock, we soon moved on. Startups should do the same. It’s going to be hard to scale your business and all the odds are against you, so celebrate wins even when they’re small. Celebrate big wins too but – and this especially relates to what you might see as big wins – celebrate then keep going. It is not the role of the startup to get comfortable. Comfort is for the slow-moving corporates. If you’ve raised money, it’s time to work double as hard to ensure you deliver to investors and have them re-invest or help you find investment to scale further. There might not be a clock ticking down to zero in your office, but be sure: you are against the clock, if you don’t move fast enough then someone else will. A couple of weeks ago, we wrote a blog about Metrics that Matter, which among other things warned of using cumulative revenue charts. This got us thinking about other charts and graphs that we’ve seen in pitch decks and presentations. Some have been excellent, while others have been distracting and confusing (two things you don’t want your pitch to be!). Therefore, we decided to share some thoughts and recommendations on the types of charts you should and shouldn’t use. First, a very quick introduction to data visualisation (i.e. charts, graphs, tables, etc.). We use visual aids to make it easier to show a trend or phenomenon. If you’ve made a super complex chart that takes more than a few seconds to understand, you’ve failed at data visualisation. This is a comforting thing to be aware of: if you struggle to understand a chart, it’s not you, it’s the chart’s design. Let’s add some rules to what makes a good chart: 1. Efficient- this is like “easier”, it should be easy to read and more efficient than the alternative of writing it out (i.e. a table); 2. Meaningful- pick data that means something, just as investors care more about how much revenue you’ve generated rather than the average time of bathroom breaks your employees take; 3. Unambiguous- if it’s not clear what the data is, then it probably needs a label or shouldn’t be there! Now that we have the rules mapped out, let’s look at some bad charts. What’s wrong with the chart below? For a start, try guessing what the value is for Sagaing in 2003. If that’s not hard enough, try to then compare that to the value of Mandalay in 2010. Now, quickly glance and say which is higher overall, Shan or Kayin. All in all, this graph is impossible to read because the 3D design hides things, colours of series are the same (or very similar) and there’s just too many datapoints. This chart fails all three rules. Let’s take a look at the chart below for another example of bad charts. We’ll let you decide why this one is bad (if you need a hint, just time yourself while you try to work out what’s going on). Not all charts will be so terrible that you recognise them as “bad charts” from the beginning. While it’s pretty easy to avoid making charts that look like those above, there’s a long way between not making those and making good charts. We try to keep our blogs to around 500-600 words, so in the next 150, we’ll set some rules to make life even easier when representing data. A) Don’t use pie charts Simplest rule is don’t use them. If you must, don’t include more than 4 segments. Never compare a pie chart to another pie chart and never, ever, use 3D pie charts. If you’re not sure, revert to the title of this rule. B) Order your data Annual data should typically be presented chronologically, but other data should be presented in a structured way: smaller numbers running to larger numbers, or vice versa – this makes patterns much easier to spot. C) Forget grid lines, use data labels (and bigger fonts) Remember, the idea is to make it easier to read a chart than a table. Looking for the biggest column / bar then checking the axis value and running your eyes along to see the column / bar value is a lot of looking around; instead, use well placed, easy to read data labels. If you want to learn more about good and bad charts, you’re in luck. There are two wonderful resources on the subject we would highly recommend:

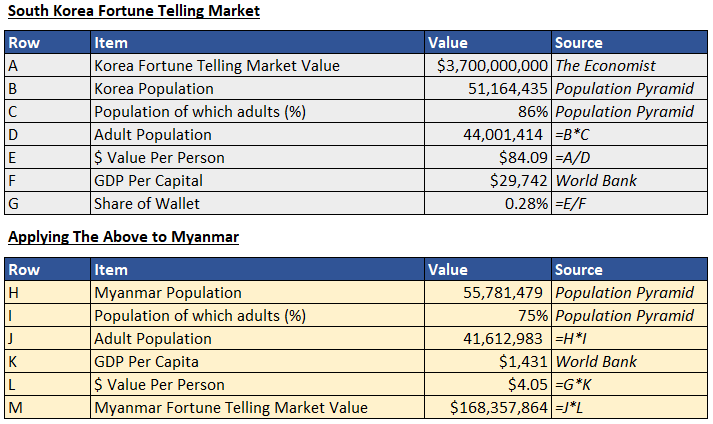

We helped Bagan Innovation Technology estimate the Myanmar market size for fortune telling and now we’re sharing how we did that.

It’s a common sight at startup pitch events all over the world (including here in Myanmar): a founder talks about their product and traction and then claims the market size for their product is hundreds of millions (or billions, especially in larger markets). If the entrepreneur can access just a tiny percent of the total market, they can achieve revenues of $2-3m in the next two years, even though revenues today are non-existent. We can’t blame entrepreneurs for this: with a few minutes to impress, they need to use big numbers and we’re always telling entrepreneurs to think big. But things can often fall apart when the entrepreneur is questioned about their assumptions behind the market figures. Market sizing is the process of estimating the total dollar potential of a market. Simply put, how much money is spent in total in your target market? Example: we estimate that the total amount of money spent on fortune telling services in Myanmar is around $200m. You’ve probably heard about TAM, SAM and maybe SOM. These are Total Addressable Market (TAM), Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM) and Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM). There’s plenty of definitions for these elsewhere so we’ll skip over them today, just know we’re talking about how to estimate the Total Addressable Market, which is total annual revenues in a market – this is the first number you’ll need before estimating anything else. Top down or Bottom Up There are two approaches to estimating market size: top down and bottom up. Top down approaches start with a big number and – you guessed it – work down. If we know the total amount people spend on grocery shopping, we can make some assumptions about how much people spend on particular products (i.e. 5% of their shopping basket is onions, so the market size for onions is 5% of the grocery shopping market). However, in Myanmar good data points can be hard to come by. What we often do, therefore, is look for a comparison country and work back. In our example, we saw that The Economist (a reputable newspaper) claimed the market for fortune telling in South Korea will soon be $3.7bn. Top Down Now, Korea has a similar size population to Myanmar, but incomes are much higher. Therefore, we want to find a way to apply the Korea results to Myanmar. Here’s how we did it: we worked out how much % of their income Koreans adults spent on fortune telling and applied this to Myanmar adults. The result was that people spend around 0.28% of their annual income on fortune telling. In Myanmar, that’s a $168m market.

Bottom Up

Bottom up approaches start from the smallest number and work up. If we’re talking about onions, we’d find the price of one onion, then estimate how many onions people bought on average each time they shopped, how many times a year they shop, etc. until we got to the total market value for onions. For fortune telling, we did the same: take the average price for fortune telling in Myanmar, how many times would people go to a fortune teller in a year, and how much of the population uses a fortune teller. This approach gives us a total market of $222m.

Which approach to use?